What are Indigenous Rights in Canada?

There is no simple definition of Indigenous rights in Canada because of the diversity among Indigenous peoples. For example, First Nations that have signed treaties with the federal government may enjoy certain privileges (such as annual cash payments) that non-treaty nations do not. Similarly, Indigenous nations that have won court cases regarding land claims may exercise more control over their lands and populations than others. In general, however, all Indigenous peoples have rights that may include access to ancestral lands and resources, and the right to self-government.

In addition to treaties, which are supposed to enshrine certain rights to land, resources and more, federal law also protects Indigenous rights, namely the Constitution Act, 1982 (see Constitution of Canada). Since 2008, the rights of First Nations people living on reserve have also been covered by the Canadian Human Rights Act. Supreme Court cases have clarified definitions of Indigenous rights, and particularly Indigenous rights (or title) to traditional territories. For example, the Delgamuukw case in 1997 showed that Aboriginal title constituted an ancestral right protected by the Constitution.

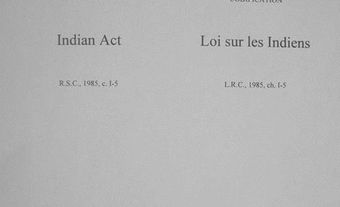

The Indian Act— another federal law — does not enshrine rights (quite the contrary, it has been historically oppressive), but it has impacted Indigenous rights. The Indian Act creates legal categories of Status and Non-Status Indians that have caused division among Indigenous peoples (see The White Paper, 1969 and Indigenous Women and the Franchise.) For example, Status Indians have certain rights that Non-Status Indians do not, such as the right to not pay federal or provincial taxes on certain goods and services while living or working on reserves. However, many Indigenous peoples (both Status and Non-Status) refuse to be defined by this federal law.

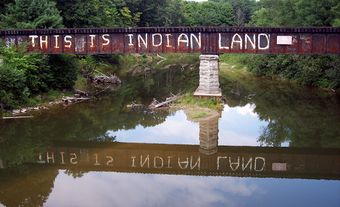

Indigenous rights are upheld and challenged at the provincial and local levels as well. Many First Nations have signed land claim agreements with federal and provincial governments. When rights to territory are challenged, relations between these groups become less amicable. The Oka crisis and Ipperwash crisis are but two instances where provincial and local authorities ignored Indigenous claims to ancestral lands. Since the arrival of Europeans, Indigenous peoples have had to protect their rights, lands, peoples and ways of life.

Sources of Indigenous Rights

Indigenous peoples have traditionally pointed to three principal arguments to establish their rights: international law, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 (as well as treaties that have since followed) and common law as defined in Canadian courts.

On the international stage, Indigenous groups have participated in United Nations working groups concerned with Indigenous populations and minority rights. Although most nations adopted the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 2007 — an agreement that recognizes Indigenous rights to self-government, land, equality and language, as well as basic human rights — Canada only signed on in May 2016 after a change in the federal government. Canada initially refused to sign because of issues concerning land disputes and the declaration’s clauses about the duty to consult that could impact resource development. It has yet to be seen how Canada will implement this agreement.

On the national stage, the Royal Proclamation of 1763 has historically been viewed as the constitutional basis for Indigenous treaties and a source of legal rights. Affirmed by section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, the legal principles of the Royal Proclamation are still applied in modern-day treaties.

The inclusion of section 35 in the Constitution signaled a new era of judicial and political opinion on the question of Indigenous rights. This section protects a spectrum of different Indigenous and treaty rights, including legal recognition of customary practices such as marriage and adoption, the site-specific exercise of food harvesting and other rights that do not involve claims to the land itself, and assertions of ownership of traditional lands.

The courts, and more specifically, the Supreme Court of Canada, have clarified and guaranteed rights to land and resource activities as well as other issues. Since governments could not come to a consensus during constitutional negotiations about Indigenous rights, the issue was consequently left to the courts. The rulings become part of Canadian law and may alter the way that the government understands Indigenous rights. For example, the Calder case helped set the stage for many First Nations in British Columbia to launch their own land claims and cases relating to Aboriginal title.

Resource Rights

Historically, Indigenous peoples have had to prove their rights in Canadian courts. For resource rights other than Aboriginal title, the Supreme Court has held that Indigenous people must demonstrate that the right was integral to their distinctive societies and was exercised at the time of first contact with Europeans (see Van der Peet Case and Pamajewon Case.) What this means is that for practices such as fishing and hunting to be enshrined as rights, Indigenous peoples must prove that these activities were practiced before the arrival of Europeans. The courts have seen commercial trade in furs and fish, for example, as the product of European contact rather than integral to Indigenous societies prior to contact. Fishing for food, community, or ceremonial purposes is, however, a protected right and may be exercised in a modern way with modern fishing equipment.

Indigenous peoples have used section 35 of the Constitution Act to support their rights to resource activities, such as fishing. In the Sparrow case (1990) — the first decision by the Supreme Court to interpret section 35 — an Indigenous person fished contrary to the provisions of federal law. In his defense, he alleged that the right to fish was an immemorial right protected by treaty by virtue of section 35. The Supreme Court upheld the right and set out a code of interpretation for section 35. The court did not set limits on the types of rights that can be categorized as Indigenous rights and emphasized that the rights must be interpreted flexibly in a manner “sensitive to the aboriginal perspective.” The court stated that section 35 only protects rights that were not extinguished (i.e. surrendered) prior to the date the Constitution Act, 1982, came into effect.

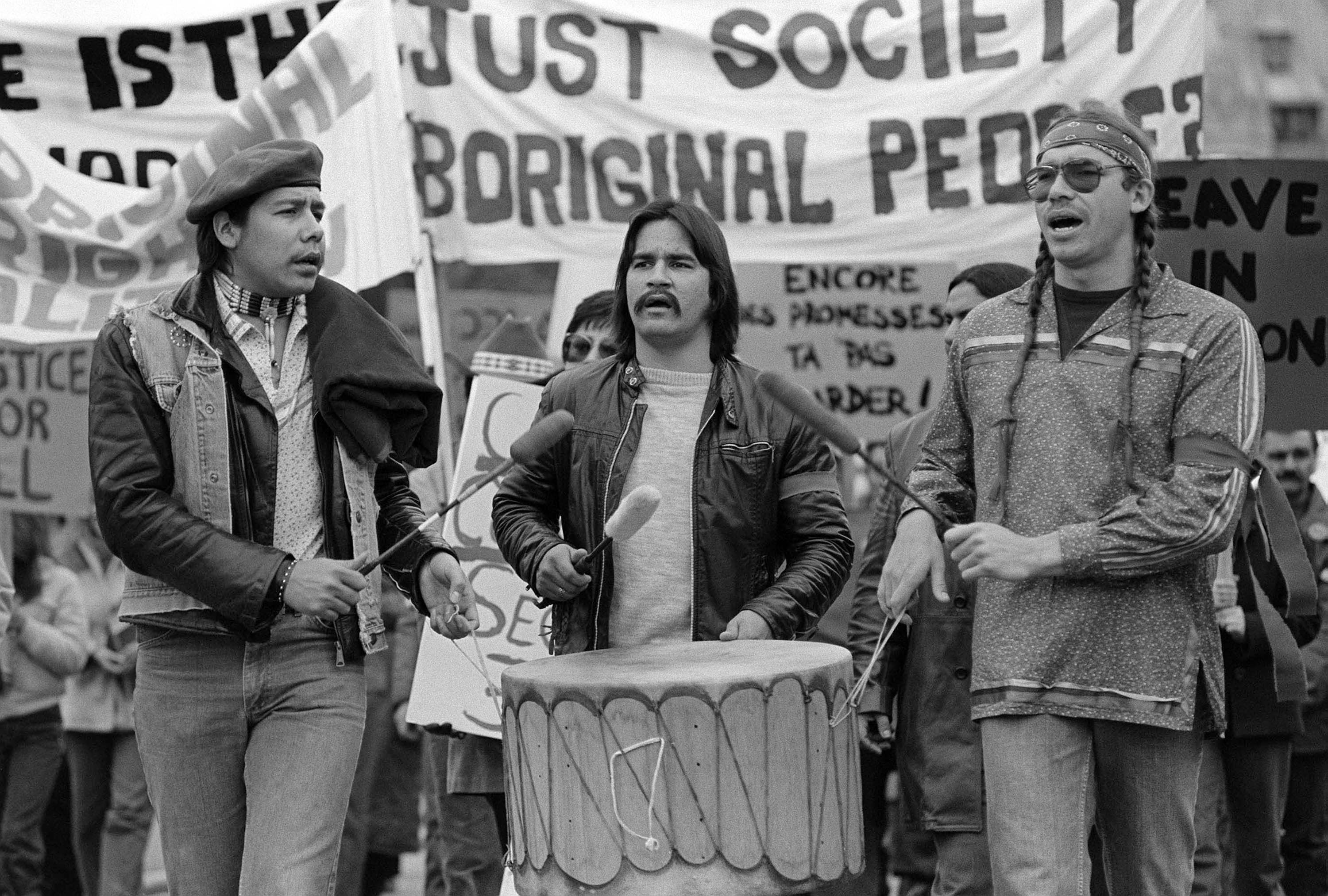

Indigenous peoples have also defended their lands and rights to resources outside the courts. Protests against development companies and the government that seek to infringe on ancestral rights have demonstrated Indigenous resistance and the desire for consultation and open dialogue about matters that affect traditional lands and rights. Some well-known examples of such demonstrations include Idle No More, the War in the Woods (1984 to 1993), a protest led by the Tla-o-qui-aht and their allies against logging and deforestation in ancient forests, and protests against pipeline developments, such as the Mackenzie Valley and Keystone XL pipelines (see Pipelines in Canada).

Aboriginal Title

There have been a few key court cases that have helped to define Aboriginal title. The Calder case (1973) recognized for the first time that Aboriginal title has a place in Canadian law. In the Delgamuukw case (1997), the Supreme Court ruled that claims to traditional lands had to show exclusive occupation of the territory by a defined Aboriginal society at the time the Crown asserted sovereignty over that territory. In the same case, the court ruled that the oral histories of Aboriginal peoples were to be accepted as evidence proving historic use and occupation. The Tsilhqot’in case (2014) further clarified the requirements for establishing Aboriginal title. The criteria for Aboriginal title are threefold: in short, an Aboriginal group must first prove occupation, and then must prove continuity and exclusivity of said occupation.

However, the court has not fully resolved all legal issues concerning Aboriginal title. Serious disputes have arisen over whether or not Aboriginal title carries with it the exclusive right to use and occupy lands. This is an issue in cases where the current occupation is not exclusively Indigenous people and where resource companies and other interests seek to carry on or expand their own uses of the same lands. Several court cases, including those involving the Nuu-chah-nulth in British Columbia, have already been launched over these issues. In most cases, the rulings ensure that proper administrative requirements are met, while permitting resource exploitation and development to continue in the overall public interest. The duty to consult was affirmed by the Supreme Court in the Delgammuuk case and is also a key part of the UN Declaration on Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Rights to Self-Government

Although Indigenous rights have yet to be given a comprehensive definition in law, most Indigenous peoples assert that they include the right to self-government. The Supreme Court has not directly addressed that issue. This was, however, a subject extensively studied by the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples, which reported to the federal government in 1996. The Royal Commission proposed solutions for a new and better relationship between Indigenous peoples and the Canadian government, including recognition of the right of self-government, settlement of land claims, measures to eliminate inequities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada and the creation of Indigenous justice systems.

One of the most well-known examples regarding self-government in Canada is the Nisga’a Final Agreement, signed after 25 years of negotiation following the Calder case in 1973 (see Nisga’a.) The content of the treaty and the ratification process were subjected to intense debate and were challenged in court. Upon Parliament’s passage of the Act in 2000, the treaty became the first modern-day treaty in British Columbia and the 14th modern-day treaty in Canada to be negotiated from 1975–2000. The Nisga’a Final Agreement gave the First Nation the right to self-government within the 2,019 km2 in the Nass Valley to which the Nisga’a hold title. Since 1973, there have been 26 comprehensive land claims and four self-government agreements (as of 2015.)

The Nisga’a Final Agreement was groundbreaking for the British Columbia treaty process because it achieved the aspirations for a negotiated settlement as expressed by the courts in the Delgamuukw case. Other First Nations in British Columbia continue negotiations of their claims. The Tsawwassen First Nation and the Maa-nulth First Nations finalized agreements in 2009 and 2011, respectively. As of July 2017, there were 58 ongoing comprehensive claims negotiations in British Columbia and another seven claims in the implementation process.

Content of Indigenous Rights

No Indigenous right, even though constitutionally protected, is absolute in Canadian law. Fishing rights, for example, are not exclusive in the sense that only Indigenous peoples can exercise them. Also, Indigenous rights are not immune to regulation by other governments. Additionally, Aboriginal title may give rise to an exclusive right to use and occupy lands, but that right may be infringed upon by the government for purposes such as economic development, power generation or the protection of the environment or endangered species. However, non-Indigenous governments must justify infringement of Aboriginal rights or title on the basis of a legitimate government purpose and recognition of the constitutional protection of the rights being affected. There may also be a requirement for prior consultation with the Indigenous peoples concerned and compensation in some circumstances.

Duty to Consult

The duty to consult — and the issue of what levels of government are entitled or required to consult — has been further explored in two 2014 Supreme Court cases, Grassy Narrows and Tsilhqot’in. In Ontario, the Grassy Narrows case pushed forward the notion that provincial governments may also “take up” treaty lands for development, but in doing so, they also take on the federal government’s responsibilities to consult with Indigenous peoples.

In the Tsilhqot’in case, the Supreme Court recognized the First Nation’s Aboriginal title and authority over 1,750 km2 of their traditional territory in the British Columbia interior. In taking an expansive view of Aboriginal title, the Supreme Court charted a new course relative to future resource development and the process of consulting with Indigenous groups in areas of Canada that have not been ceded by historic treaties. This suggests that the Crown in future must do more than fulfill a duty to consult. It must also either obtain consent or meet legal requirements to justify infringing on Indigenous rights.

Indigenous Women’s Rights

During the 1970s and 1980s, Indigenous women launched a number of cases against the federal government concerning the legal and gender discrimination inherent in the Indian Act. Since 1869, Status Indian women who married Non-Status Indian men lost any treaty and Indigenous rights that they previously enjoyed (see Indigenous Women and the Franchise). In 1985, Bill C-31 amended the Indian Act to remove the discrimination and bring the act in line with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The 1985 amendment allows women who “married out” to apply for the restoration of their status and rights, and also allows their children to apply for registration as Status Indians. The Act no longer requires or allows women to follow their husbands into or out of status, and it allows women to pass status on to their children just as men always have.

However, while the amendment addressed much of the former discrimination against women, it also created some problems. By placing these women, and often their children, onto First Nations band membership lists, the government stretched already limited lands and funds to serve more people, and this has at times incited resentment and backlash toward these “Bill C-31s” by First Nations members.

Further, the inclusion of a “second-generation cut-off” rule potentially means a great reduction in the number of people entitled to be registered as Status Indians under the Indian Act. According to Bill C-31, there are two categories of Indian registration. The first, known as sub-section 6(1), applies when both parents are or were entitled to registration. The second, known as sub-section 6(2), applies when one parent is entitled to registration under 6(1.) Status cannot be transferred, however, if that one parent is registered under sub-section 6(2.) In short, after two generations of intermarriage with Non-Status partners, children would no longer be eligible for status. Moreover, for a child to be registered, both the mother’s and father’s names must be included on the birth certificate. If the father’s name is not included, he is assumed to be Non-Status. In such situations, children born to women registered under sub-section 6(2) are not eligible for status. The amendment therefore significantly limits the ability to transfer status to one’s children.

Bill C-31 also did away with the “double mother rule,” which had conferred status on non-married individuals up to 21 years of age whose mother and paternal grandmother were Non-Status. However, eliminating the effects of this rule created a new inequality that made it difficult to transmit status in certain cases.

In response to the British Columbia Court of Appeal ruling in McIvor v. Canada (2009), Bill C-3, passed in 2010, attempted to ensure parity of status for grandchildren of women who “married out” and those affected by the “double mother” rule. Currently before Parliament, Bill S-3 is attempting to address disparity in who is entitled register as a 6(1) and 6(2) Indian. Bill S-3 was a response to the Québec Superior Court ruling in Descheneaux v. Canada in 2015.

Extinguishment of Indigenous Rights

The “extinguishment” of rights means the taking away or surrendering of rights. Historically, treaties or land claims settlements have served to extinguish Indigenous rights. All courts have recognized the power of Parliament to extinguish Aboriginal rights and title up to 1982, but this was never expressly done. Indigenous rights to hunt and fish, however, have been limited by constitutional amendment, federal legislation, and in some instances by provincial laws. In the 1990 Sparrow decision, the Supreme Court ruled that rights could be regulated if the regulation could be justified in the manner described above. In the Delgamuukw case, the Court did not rule out extinguishment after 1982, but made strong statements about consultation and compensation if rights are extinguished.

In the Bear Island case, a case appealed to the Supreme Court but dismissed in 1991, it was also held that delay in bringing a court action was sufficient to defeat a claim to Aboriginal title. This alone, if correct in law, would be enough to defeat almost every land claim that is brought to court. Moreover, the First Nation had signed a treaty in 1850, thereby extinguishing their rights. In the 1995 Blueberry River case, the Supreme Court applied a statutory limitation period to defeat part of a First Nation’s claim in respect to a surrender of reserve lands and mineral rights.

Historically, federal laws have also worked to deny the rights of Indigenous peoples. The Indian Act has taken away basic rights over time, such as the right to hold potlatches, dance and practice Indigenous religions. Willing or forcible enfranchisement (the processes by which Indigenous peoples lost their status under the Indian Act) extinguished Indigenous rights in exchange for others as Canadian citizens (see Indigenous Suffrage.) Other federal legislation has also worked to assimilate Indigenous peoples and therefore deny them their rights, such as residential school and the pass system (a policy in which Indigenous peoples who wished to leave their reserve, even temporarily, had to acquire a pass from an Indian agent before leaving).

Métis Rights

Métis rights have largely been defined and clarified by the courts. A particularly important case is R. v. Powley (2003), which affirmed the Métis ancestral right to hunting for sustenance. Powley was the first case in which the Supreme Court affirmed the existence of Métis rights. The case also established a test to determine Métis rights under section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982. The Powley test has 10 criteria that determine Métis identity and if a Métis community has an existing right to an activity, such as hunting.

The identity part of the test consists of three criteria: to be considered Métis, individuals must identify as Métis, be a member of a modern Métis community and have ties to a historic Métis community. This last requirement also asks that individuals prove another set of criteria: that their mixed ancestry group formed a “distinctive” collective social identity, that they lived together in the same geographic area and that they shared a common way of life.

The Powley case therefore confirmed the definition of Métis as one that is specific to a distinct community of peoples rather than anyone who has mixed Indigenous and European heritage. To those who consider themselves Métis but do not fit this description – namely those living outside the territory as defined by the Métis National Council, including Alberta, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and parts of Ontario, British Columbia and the Northwest Territories– they feel the Powley decision denies their Indigenous identity. However, to those who can trace their lineage to specific, historic Métis communities, the Powley case validates their long-standing argument that they are a distinct Indigenous community (see Métis Are A People, Not a Historical Process and The “Other” Métis.)

The Daniels court case (2016) is also significant to Métis rights. On 14 April 2016, the Supreme Court ruled in the Daniels decision unanimously that the legal definition of “Indian” — as laid out in the Constitution — now includes the Métis and Non-Status Indians. This ruling will facilitate possible negotiations over traditional land rights, access to education and health programs, and other government services. This ruling did not, however, grant Indian status to any Métis or Non-Status Indian people.

Inuit Rights

The Inuit fall under the category of “Indian” in the Constitution Act, 1982, and are therefore also protected by section 35. However, the Inuit have never been subject to the Indian Act and were largely ignored by the federal government until 1939, when a court decision ruled that they were a federal responsibility, though still not subject to the Indian Act. Policies of assimilation followed, including forced relocations into sedentary communities and the introduction of disk numbers for administrative purposes (see Project Surname and Hebron Mission National Historic Site of Canada).

Various treaties and land claims have confirmed Inuit rights to land title in northern Canada, including the James Bay and Northern Québec Agreement (1975), the Western Arctic (Inuvialuit) Claims Settlement Act (1984), the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement Act (1993) and the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement (2005.) Together, these four regions cover about 40 per cent of Canada’s land mass.

An important court case concerning Inuit rights is the Clyde River case (2017.) The Inuit living in and around Clyde River, Nunavut, vehemently opposed the plans of the National Energy Board (NEB) to conduct seismic testing for oil and gas deposits near their community since it was first proposed in 2011. Taking their case to the Supreme Court, the Clyde River Inuit emerged victorious: the judges unanimously decided that the NEB failed to properly consult the Inuit about their plans and did not adequately assess the effect that seismic testing would have on the rights of Indigenous peoples. Quashing the NEB’s approval, the Supreme Court put an end to the seismic testing. While the court did not create guidelines for how to consult with an Indigenous community, this case highlights the importance of consultation.

On the international stage, Inuit peoples have had their rights to Arctic lands and waters affirmed by such declarations as the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Looking Forward

The content and priority of issues surrounding Indigenous rights and title continue to evolve judicially and through the negotiation and implementation of self-government agreements between Indigenous peoples and the Government of Canada. Over the long term, it is likely that these issues will need to be addressed through negotiated political resolution.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom