There are six cultural areas contained in what is now Canada, unrestricted by international boundaries. The Plateau cultural area consists of the high plateau between the British Columbia coastal mountains and the Rocky Mountains, and extends south to include parts of Washington State, Oregon, Idaho, and Montana. At lower elevations it is comprised of grasslands and subarctic forests. Plateau Indigenous peoples include, among others, the Secwepemc, Stl’atl’imc, Ktunaxa, and Tsilhqot’in. (See also Interior Salish.)

First Nations and Language Families

The linguistic families traditionally represented in the Plateau are the Dene (sometimes known as Athapaskan or Athabaskan) and Salishan languages. Some subsidiary languages are now extinct, while others are supported by a number of language programs and native speakers.

In the Plateau, Interior Salish First Nations include the Secwepemc (or Shuswap), Stl’atl’imc (or Lillooet Stl’atl’imc), Nlaka'pamux (sometimes known as Thompson), and Okanagan (or Syilx). The Ktunaxa peoples (also known as Kutenai or Kootenay), whose traditional language is an isolate, are based along the western edge of the Rocky Mountains in the Kootenay River basin; this region is now known generally as “Kootenay” or “the Kootenays.” The Tsilhqot’in (Chilcotin) and Dakelh(or Carrier), both Dene groups, inhabit the northern area Plateau. The Stl’atl’imc and Nlaka’pamux areas are found along the southwestern edge of the Plateau, abutting the Coast Mountain Range. The Secwepemc inhabit the large central territory west of the Rocky Mountains, north of the Kootenays, looping over traditional Okanagan territory in the Okanagan Valley.

Did You Know?

Archaeologists postulate that at least 10,000 years ago, not long after the glaciers from the most recent ice age receded, the British Columbia Plateau was populated by Indigenous peoples who had migrated northward from more southerly areas of this same Plateau. (See also Prehistory.) Gradually there emerged a culture adapted to the forested mountains, sage- and cactus-covered hills, and riverine resources of the area.

Traditional Life

Migration

In this region, groups of related people worked and travelled together in the spring, summer and fall, then joined with other such groups to reside in relatively permanent winter villages. Plateau society was egalitarian and communal in most respects, although men were the major decision makers. Within each village there were a number of chiefs, or headmen, who organized economic activities — there was a salmon chief for fishing, and so on. The advice of these men was taken seriously, but every adult male took part in gatherings to discuss the general concerns of the group. In some areas of the Plateau a council of elders was drawn from the community at large; when confronted with an issue affecting the band, a headman invited other males to discuss it. Often, decisions were made primarily on the advice of elders.

Division of Labour

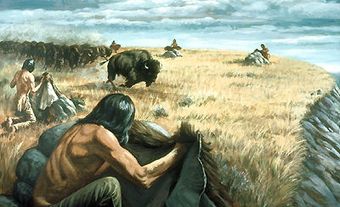

Indigenous peoples on the Plateau divided labour based on gender. Men were responsible for hunting, trapping, fishing and manufacturing implements from bone, wood and stone, and also for warfare. Women's responsibilities included preparing food for meals and for winter storage, harvesting plants, maintaining the home and caring for small children. There was little formal specialization of roles. Those men who had acquired certain physical and spiritual abilities during their adolescent training became"professional" hunters of bear and mountain goat. All men were expected to be competent deer hunters.

Land and Resources

Land and resources were considered communal property, with a few exceptions. Some salmon-fishing stations were owned by individuals, while others were owned collectively by resident or village groups. Remote hunting grounds and root-harvesting grounds were generally open to all those who spoke the same language, and inhabitants of a specific area sometimes gave consent to use these areas to others. Obligatory sharing and economic egalitarianism formed the basic ethos of the society. Some groups of Secwepemc and Stl’atl’imc had a system of hereditary stewardship that associated certain hunters with areas they knew well.

Food

The people of the Plateau relied primarily on hunting and trapping to acquire goods but also traded their fish, furs, tools and weapons. They hunted large animals using pitfall and deadfall traps, used bows and arrows for smaller prey and caught waterfowl with nets. Food was shared liberally among all villagers. At public salmon-fishing stations, a weir or net was used to catch fish for the entire village, and men with harpoons caught fish for their individual families' needs.

As the Plateau economy was based on seasonal hunting, fishing and gathering — each with unpredictable availability — much time and effort was spent smoking or drying food for storage. Preserving food was critical to ensure survival, and the entire community was involved in this activity.

Food was not always plentiful, however. There were occasions when the salmon runs failed, certain animals were not available, or root and berry crops did not materialize. At such times the people had to travel farther and work harder to survive. Each spring the appearance of the first run of salmon and the first fruits or berries was celebrated with a special ceremony to ensure a good harvest.

Transportation

Long distance transportation on the Plateau was done primarily by dugout canoes made from red cedar or cottonwood, or bark canoes from white pine or birch. To travel on foot in winter, Plateau peoples used snowshoes— their designs specifically suited to the varying conditions of snow and terrain. In early times, dogs were used as pack animals as well as in hunting deer. By the 1730s, the introduction of the horse from farther south dramatically improved the mobility of Plateau peoples. It is likely that the Ktunaxa were the first Plateau group in Canada to obtain horses.

Housing

Plateau peoples lived in three main house types: the semi-subterranean pit house, the tule-mat lodge and the tipi. The Plateau peoples were semi-nomadic and their dwellings were constructed from portable, reusable materials. Other structures included a sweat lodge for men and a menstrual isolation place for women. Both structures served as ceremonial places to transition into adulthood. Upon first menstruation, for instance, a girl would be sequestered for about one week, and then attended to by elders and furnished with gifts.

Traditional-style dwellings were generally last used in the Canadian Plateau around the mid- to late 1800s, although in some areas their use extended into the early 1900s. (See also Architectural History of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

Clothing

On the Plateau, Indigenous peoples made clothing sewn from the tanned hides of animals and woven from local grasses or from the pounded bark of bushes. Moccasins were common; most often they were made from deer hide, but occasionally from salmon skin. Winter clothing consisted of the thick skins of fur-bearing animals. Some groups decorated clothing with dentalia shells, ochre paint, porcupine quills or handmade beads or seeds. Mats and baskets woven for utilitarian purposes were often similarly adorned.

Songs

Songs were important in traditional Plateau life and were used by individuals to summon religious and magical powers. Singing was sometimes accompanied by wooden flutes, rattles of deer hooves, but mainly by hide-covered wooden-frame drums. One type of song still known and widely performed today is the stick-game song, often sung while playing a gambling game.

Oral Traditions and Language

Plateau peoples transferred traditional knowledge to succeeding generations via oral tradition. The history of a community was passed from generation to generation using detailed descriptions of events and people. The language and context of the story were part of its meaning and purpose. A complex cycle of tales, frequently with humorous and bawdy episodes, involved the trickster-creator known as Coyote. Language and oral tradition are naturally linked, and therefore contemporary language revitalization efforts among Plateau peoples also tend to focus on the importance of oral traditions. (See also Oral History and Indigenous Oral Histories and Primary Sources.)

One of the most significant cultural changes after European contact was the introduction of written systems. Hudson's Bay Company officials and early missionaries attempted to introduce literacy and calendars, but to little effect. In the late 19th century, Father Jean-Marie-Raphael Le Jeune (1855–1930), a Catholic missionary, made the most significant impact in helping to establish written systems of Indigenous languages on the Plateau. However, much of the Plateau peoples’ culture and language, both oral and written, was lost through generations of assimilative practices such as the residential school system. (See also Indigenous Languages in Canada.)

Spiritual Beliefs

Plateau peoples maintained a deep connection with their environment. Everything around them was imbued with special powers. This spiritual relationship with nature permeated all aspects of daily life. (See also Spirituality and Religion of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

During adolescence, every individual underwent special training to receive guardian-spirit power from a nature-helper. The spirit came to the person when he or she was in a trancelike state, told the recipient how to use the gift and provided a "power song." Shamans trained longer and more intensively and received special powers enabling them to cure the sick or cause harm to others, and were both respected and feared. They used their guardian-spirit powers in curing rituals.

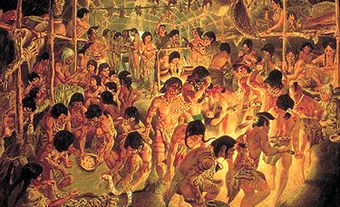

The guardian-spirit dance, usually performed in the winter, was a major ceremony for most Plateau peoples in what is now the United States as well as Okanagan. The dance was likely celebrated in former times by the Secwepemc, Nlaka’pamux and Stl’atl’imc, although in a slightly different manner. Some Okanagan people still participate in similar ceremonies today in both British Columbia and the US. Shamans host the dance and use the occasion to communicate their spirit powers in public. After one or several nights of dancing and administering to the needs of the sick, the host or hostess presents their guests with gifts. Other Salishan groups in the Plateau held similar ceremonies, marked by the singing of spirit songs, at any time of the year.

Among the Ktunaxa, a ceremony was held that united a spirit power and its possessor for such purposes as predicting future events and finding lost objects. This ceremony, along with the Sun Dance, points to the relationship of the Ktunaxa people with the Plains Indigenous peoples.

For a time, several Plateau groups adopted Christianity, largely due to the influence of missionaries and the imposition of assimilative residential schools by the federal government from the late 19th century onward. As Indigenous groups on the Plateau have fought for political and cultural restoration, several groups have made efforts to restore traditional religious beliefs and ceremonies.

European Contact and Colonial History

The Plateau's abundant natural resources were the major stimulus that attracted non-Indigenous people to this area. The lure of furs brought the explorer Alexander Mackenzie into contact with the Northern Secwepemc people in 1793, and David Thompson into Ktunaxa country in 1807. (See also Fur Trade in Canada.) In 1808 Simon Fraser explored the river that now bears his name. These explorers were received hospitably by the Indigenous peoples they encountered. For example, a chief took Fraser by the arm and directed him to shake hands with each of the 1,200 Nlaka’pamux people assembled at Lytton to meet him.

By the 1820s, fur-trading posts had been established throughout the Plateau. With the introduction of firearms and metal implements, the hunting of fur-bearing animals such as deer, elk (wapiti), bears, and bison became much more efficient, and soon the numbers of these animals dwindled. At the same time, diseases such as measles, influenza and smallpox swept through Indigenous settlements, killing thousands.

Gold was the impetus for the next wave of non-Indigenous people to overrun the Plateau. The discovery of gold in 1857 on the Fraser River attracted over 30,000 white fortune seekers to the area, the vast majority of whom arrived from gold mining areas in California. In an effort to establish a peaceful relationship between peoples and to protect Indigenous lands from further encroachment, the colonial governor of British Columbia, James Douglas, attempted to establish policies that would respect Indigenous land rights. Douglas sought to establish treaty-based reserves within the homelands of First Nations, rather than pursuing the policy of removal and concentration that had characterized the settlement of the western US. Indigenous peoples would then live on reserves surveyed and administrated by the government. Douglas’s tenure expired in 1864, however, and settlement policies became dominated by the new chief commissioner for lands and works, Joseph William Trutch, who refused to recognize Aboriginal title and sought to requisition as much of their land as possible.

On the Plateau, no treaties were signed and no compensation was paid, although reserves were allotted and surveyed beginning in 1858. Many large reserves established during the colonial period were subsequently reduced after British Columbia joined Confederation in 1871. (See also British Columbia and Confederation.) By the late 1890s, the Plateau peoples had been assigned to live on scattered, small reserves. Provincial officials declared the Royal Proclamation of 1763 inapplicable to British Columbia and indeed were skeptical that Aboriginal title even existed. Indigenous rights were frequently marginalized, leading to a number of continuing efforts to reclaim traditional lands and methods of self-governance. For example, the Allied Tribes of British Columbia, a partnership between the Nisga’a, Coast Salish and Interior Salish, was formed in 1916 to oppose the increased practice of reserve reduction undertaken by a succession of provincially sanctioned land commissions. However, this initiative was overshadowed by an ongoing conflict between the province, which, following the precedent set by Trutch, sought to continue land appropriations, and the federal government, which claimed Crown title to the reserves. To resolve the dispute, in 1912 the government established the McKenna–McBride Commission, which released a report recognizing most of the existing reserves and recommending that some additional land be set aside. The government ratified the report without consulting the affected Indigenous populations — ultimately taking land away from some First Nations while giving more to others. In 1969, the federal government acknowledged the improper nature of such land seizures, resulting in the first land claim settlements in 1982.

Contemporary Issues

Since the establishment of reserves in the late 19th century, Plateau peoples have played a major role in struggles relating to land claims in British Columbia. Secwepemc leader Basil David joined Indigenous delegations that travelled to Britain in 1906 and to Ottawa in 1912 to present land grievances to the Crown. The influential Indigenous organization the Allied Tribes of British Columbia was established in 1916 by several Interior Salish First Nations. This organization was active until 1927, when it collapsed following a failed attempt to claim Aboriginal title through the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.

Since the early 1970s many Plateau peoples have made a conscious attempt to reinterpret traditional ways. The mid- to late 1970s saw the establishment of powerful Indigenous councils in the Canadian Plateau, organized along linguistically defined lines and consisting of several bands. Both the bands and the tribal councils are strong advocates of Indigenous self-government, the economic development of reserve lands, educational opportunities for Indigenous people, cultural and linguistic survival and equitable settlement of the long-standing land-claims issues with both federal and provincial governments. In many groups, strong movements toward cultural revitalization are underway, with focus on education, language and traditional knowledge.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom