Prior to colonization, Indigenous Peoples possessed rich and diverse healing systems. Settlers’ introduction of new and contagious diseases placed these healing systems under considerable strain. Europeans also brought profound social, economic and political changes to the well-being of Indigenous communities. These changes continue to affect the health of Indigenous Peoples in Canada today. (See also Social Conditions of Indigenous Peoples in Canada and Economic Conditions of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

Indigenous Health and Healing

Traditionally, Indigenous Peoples in Canada used healing practices that were (and are) place based and shaped by the needs of the people living in those territories. For example, Inuit had numerous treatments related to frost bite and hypothermia. (See also Cold Weather Injuries.) The natural environment shaped the medical expertise and practices used by Indigenous Peoples.

The arrival of Europeans to North America introduced unfamiliar diseases, such as smallpox and influenza, that strained Indigenous healing systems. (See also Epidemics in Canada.) However, Indigenous modes of healing eventually adapted. Indigenous communities reacted to disease very differently, and these responses varied over time and geography.

Indigenous health and wellness practices were forced to operate under colonial structures. Amendments to the Indian Act in the late 19th and early 20th centuries criminalized and prohibited Indigenous healing practices. These laws, combined with poor living conditions, poverty, racism, loss of land and declining access to food resources, had devastating consequences on the health of Indigenous Peoples.

As Indigenous nations fight to reassert their sovereignty, many therapeutic practices persist. In addition, some Indigenous health service organizations have adopted healing models that embrace both Indigenous and Western knowledges and worldviews.

Social Determinants of Health

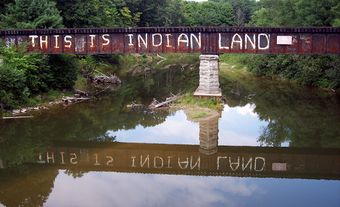

Social determinants of health are specific social and economic indicators that relate to a person’s place in society that influence people’s health. These include, for example, access to safe housing and food, quality of education and health care, and access to other social services. For Indigenous Peoples in Canada, settler colonialism has created the conditions that have led to disproportionately poorer health outcomes. For example, rates of food insecurity in Indigenous communities are higher than the national average. This is a direct result of federal and provincial policies that prevented and reduced access to food and land based medicines that had maintained Indigenous people’s health and well-being for generations. (See also Indigenous Peoples’ Medicines.)

On reserves, infant mortality rates (IMR) vary from three to seven times the national average. Off reserves, Indigenous populations tend to have an IMR two to four times higher than the non-Indigenous population. Growing up, Indigenous children are four times more likely to be hungry than non-Indigenous children and also have a 40 per cent chance of living below the poverty line. A high IMR, in combination with malnutrition and poor access to healthcare, causes Indigenous children to live with or die from chronic diseases more often than other Canadian children, and these trends persist into adulthood.

Type-II diabetes is perhaps the most troubling and widespread chronic illness affecting Indigenous Peoples and is directly related to historical trauma and ongoing land dispossession. Studies have demonstrated that type-II diabetes continues to be two to five times more common amongst Indigenous people than the wider population. Given the high cost of food in isolated and northern areas and the high rates of food insecurity that disproportionately affect Indigenous people generally, these rates are unsurprising.

The health status of Indigenous people is further affected by poor housing. On-reserve homes are three times more likely to be in need of major repair than Indigenous homes off-reserve, and six times more likely that non-Indigenous homes. Additionally, 37 per cent of First Nations on reserve and 40 per cent of the Inuit population in the north live in crowded housing. Studies have shown that people who live in crowded and damp and mouldy homes are at higher risk of depression, respiratory symptoms and asthma.

As these statistics demonstrate, historic and ongoing settler colonialism has ensured that unequal access to health care, when combined with racism and other social determinants, continues to have enormous and tragic consequences on the health outcomes of Indigenous people.

Western Health Care Delivery

Minimal health services were made available to Indigenous people in the late 19th century. Initially made at the request of missionary organizations, these health services were meant to contain ill-health they feared Indigenous communities might spread to white settlements.

As part of negotiations for Treaty 6, Chiefs brought forward terms related to healthcare. Their efforts resulted in Treaty 6 including a clause requiring a medicine chest be maintained at the house of the Indian Agent. Some argue this clause establishes a Treaty Right (see also Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Canada) to equal access to modern healthcare.

When the first federal Department of Health was created in 1919, it did not support or protect Indigenous communities. It was not until 1927 that a Medical Services Branch was formally created within the Department of Indian Affairs. While the federal government provided medical care to Indigenous Peoples before 1927, it was limited and basic.

After the Second World War, growing concern regarding tuberculosis rates among Indigenous peoples, and the perceived “threat Indian tuberculosis posed to the nation,” led to increased development of segregated sanatoriums and Indian Hospitals across Canada to treat Indigenous Peoples. (See also Racial Segregation of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

In the 1960s, the federal government signed a series of agreements with provincial governments to enable Indigenous people to access provincial health services off-reserve. The federal government remained in control of health care provision on-reserve and in remote areas. The last several decades have witnessed efforts by the federal government to transfer on-reserve health services to local control. However, in spite of these efforts, health care for Indigenous people in Canada remains inadequate, complex and underfunded. (See also Indigenous Services Canada.)

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom