This article was originally published in Maclean's Magazine on June 12, 1995

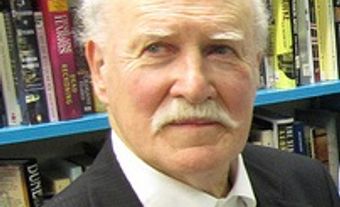

If Yevgeny Yevtushenko did not exist, another author might have invented him as the central character in one of those sweeping epics that Russian writers adore. The problem would be that, as a work of fiction, Yevtushenko's real life strains credulity. A literary superstar in Russia since his teens, he attracts stadium crowds of up to 30,000 for his poetry readings. He moonlights as an actor, director, screenwriter and political activist. And his passion for life includes filling significant parts of it in the company of women and good wine. Appropriately for someone whose achievements seem larger than life, he is, at six feet, three inches, larger than most people around him, dresses in an eclectic, electric manner that would do the lead singer of a rock band proud, and, with his famous piercing blue eyes undimmed at age 61, has just as much stage presence. As befits someone who has spent close to half a century being acclaimed, Yevtushenko has an ego in keeping with his achievements. "I am the spiritual grandchild of Pushkin," he says, cheerfully likening himself to the man generally regarded as Russia's greatest writer.

Sometimes, although not always, the quality of Yevtushenko's writing approaches the level of such a claim. As a poet, his work has ranged from the sublime, such as his 1961 epic Babi Yar - dealing with Russian and German anti-Semitism during the war - to the incomprehensible, including much of the work he did in the 1970s. Yevtushenko himself once cheerfully declared that his poetry is 70-per-cent "garbage" and 30-per-cent "OK." His new book, Don't Die Before You're Dead (Key Porter, 398 pages, $28.95), marks a turn to prose. It also lives up to another of Yevtushenko's assertions - that he reflects Russia's troubled soul. "People may like this book, or they may not," he said in the course of a recent two-hour interview in Toronto. "Either way, they should accept that it represents Russia the way it is."

On one level, its title reflects Yevtushenko's concern that Russians, inured to a life of constant fear and deprivation during the worst years of the old Soviet Union, often die a spiritual death before their physical one. It is also the advice that "Boat," the book's most vivid character, gives to her sometime lover, a former soccer star named Prokhor (Lyza) Zalyzin. Sprawling, bombastic, occasionally overwrought, and filled with black humor, Don't Die Before You're Dead sweeps through daily life in the former Soviet Union from the Second World War until the early 1990s. In the process, Yevtushenko evokes a dizzying and often brilliant panoply of emotions and characters. All are instantly recognizable to anyone familiar with the alternately challenging and deadening qualities of everyday existence in Russia.

The central event of the book is the brief real-life coup of August, 1991, by a group of hardline Communists disenchanted with the reform policies of then-President Mikhail Gorbachev. Their object was to restore the Soviet Union to its former status as a world power: in fact, more than anyone else, they hastened its dissolution.

But Yevtushenko spends little time investigating the event's historical importance. Rather, it serves as a backdrop and catalyst for the manner in which ordinary people confront an extraordinary event. The record is mixed: those who joined current Russian President Boris Yeltsin in resisting the putsch ranged from Yevtushenko himself and other favored figures in the old Soviet regime to smugglers, black market operators and those motivated by little more than a keen eye for the main chance. At the time of the coup, Yevtushenko writes, the country was, in the balance, "divided into three countries. One was frightened and wanted to return to yesterday. The second did not yet know what tomorrow would be like, but did not want to return to yesterday. The third was waiting."

Much of the public discussion of the book so far has centred on Yevtushenko's portraits of such figures as Gorbachev, former Soviet Foreign Affairs Minister Eduard Shevardnadze and President Boris Yeltsin. They are written in a breezy manner that combines some psycho-babble, such as speculation on the forces that affected Gorbachev early in life, with an easy mix of anecdote and insight that reflects the intimate access Yevtushenko had to top levels of the Soviet leadership. Yevtushenko remains, overall, a fan of all three men, despite the fact that he declined a medal from Yeltsin last year as a protest against Russian army behavior in Chechnya. "Yeltsin," he says, "is a good axe, but we need a jewel, not an axe, now." Yevtushenko also confesses regret over the breakup of the Soviet Union, "not for what it was, but for the brotherhood of different groups that it could have been."

Yevtushenko's closeness with former Soviet leaders also serves as a reminder of the suspicions that some Russians still harbor towards him. That resentment is based on the fact that he lived a privileged life in the former regime even while presenting himself as one of its most ardent internal critics. Of that, Yevtushenko says wearily, "people should look at my record. They cannot say I only pretended to criticize when the record shows so clearly that I spoke against bad policies very publicly many times."

The real charm of Don't Die Before You're Dead, and Yevtushenko's strength as a writer, lies in the skill with which he reflects the contradictory elements that vie for control of the Russian soul. The book's most enduring and endearing figures are both fictional: the middle-aged, disillusioned and alcoholic Zalyzin, and Boat, an earthy and physically imposing woman whose determination and strength of character only emphasize Zalyzin's weaknesses, and the paradox of her devotion to him. Her nickname derives from her promise to be "the boat that is always waiting for you." Still, their relationship is ultimately doomed: in less skilful hands than Yevtushenko's, their story would be soppy. But the author knows his characters too well to allow that, and their relationship is all the more compelling for the fact that he emphasizes their flaws. Yevtushenko, who has been married for nine years to his fourth wife, Masha, a physician (they have two children), says that Zalyzin "is really me." And Boat "is a woman who loved me madly, and who I did not have the good sense to love back until it was too late."

Other fictional characters include Stepan Palchikov, a Moscow police officer who joins the side of the coup resisters. He is a classic figure in detective fiction: the weary cop who buries himself in his job to hide from a disintegrating marriage. Yevtushenko himself also appears, in first person, recalling his role in the events. Few other authors would have the cheek to include themselves not once, but in two different characters, in the same book.

With his fondness for epic tragedy and layered prose, and his eagerness to mine the depths of the Russian soul, Yevtushenko is an obvious heir to a literary tradition of mega-page gloom and doom that extends back to such figures as Dostoyevsky and Pushkin. But Yevtushenko is a highly contradictory man. Despite the despair that suffuses some of his writing, he maintains a huge appetite for life. His angry impatience with the swift passing of time is coupled with concern over how much is left him. "I hate death as a monster which swallows us," he says. "I pray and pray every day that I will get at least 25 more years of life. With that, I could direct 10 more films, write five more novels."

He now spends half of each year teaching Russian studies at the University of Tulsa in Oklahoma, describing himself as "the ultimate citizen of the world." Considering that he speaks fluent English, French and Spanish as well as Russian, and that his work has been translated into more than 70 different languages, that may be true. And he delights in recounting the fact that American author John Steinbeck, shortly before his death, predicted to Yevtushenko, then known only as a poet, that he would one day become known as "a great writer of prose." "You see?" says Yevtushenko, after a great swallow from a glass of Burgundy wine, "I must have more time, to fulfil my destiny, and Steinbeck's prediction." He says that his sequel to this book, which he has already started writing, will be called Don't Die After You're Dead. And Yevtushenko hopes to take that advice personally.

Maclean's June 12, 1995

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom