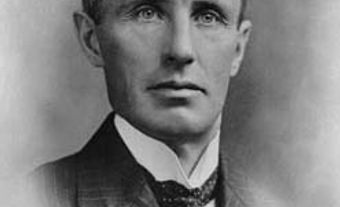

Sir Charles Tupper, prime minister, premier of Nova Scotia 1864–67, doctor (born 2 July 1821 in Amherst, NS; died 30 October 1915 in Bexleyheath, England). Charles Tupper led Nova Scotia into Confederation while he was premier. Over the course of his lengthy political career, he served as a federal Cabinet minister and diplomat, and briefly as prime minister of Canada — his 10-week term is the shortest in Canadian history. He was the last surviving Father of Confederation.

Education and Early Career

Charles Tupper was born on his family’s small farm near Amherst, Nova Scotia. His father, also called Charles, was a Baptist pastor. Largely home-schooled, Tupper’s education was supplemented by grammar school classes. In 1837, he studied at Horton Academy (later Acadia University) in Wolfville, Nova Scotia, focusing on Latin, Greek, French and science. After graduating in 1839, he spent some time teaching in New Brunswick before studying medicine in Windsor, Nova Scotia, in 1839–40. Tupper then studied at the University of Edinburgh, in Scotland, where he earned his medical degree in 1843. He returned to Amherst that year and established a medical practice and drug store.

He married Frances Morse, a descendent of the founders of Amherst, in 1846. The couple had six children.

Political Career

Charles Tupper was encouraged by a family friend and Nova Scotia Conservative party leader James William Johnston to run for a seat in the Nova Scotia Assembly as a Conservative. In 1855, Tupper dramatically unseated Cumberland County’s popular Reform representative, Joseph Howe. While the Conservatives did not fare well in the election, Tupper outlined a new party strategy in caucus that sought to court Nova Scotia’s Roman Catholic minority and bolster railway construction. By 1857, Tupper had convinced disenchanted Roman Catholic Liberals to cross the floor, which reduced the government to a minority. As a result, the Liberals resigned and the Conservatives took power on 14 February 1857. With Johnston as premier, Tupper became provincial secretary.

Tupper set out to improve Nova Scotia’s railways, believing it was vital to the development of natural resources. He also believed that railways would make the province’s major port city, Halifax, a “vast manufacturing mart for this side of the Atlantic.” In June 1857, he opened talks with officials from New Brunswick and the Province of Canada to discuss the possibility of an intercolonial railway. After sailing to London to secure backing for such a project, Tupper returned empty-handed. According to historian Phillip Buckner, this “convinced [Tupper] of the need to restructure the imperial relationship and to seek closer ties with the other British North American colonies.”

The Conservative party lost a bitter election in 1859, though Tupper retained his seat. After his party returned to power in 1863, Tupper served as provincial secretary. He became premier of Nova Scotia in May 1864.

Medical Career

Though his career in medicine was initially sidelined when he entered politics, Charles Tupper continued to practise medicine throughout his political career. While sitting in opposition, he opened a successful medical practice in Halifax in 1859. He was also at this time a hospital surgeon and municipal medical officer and involved in the development of a medical school. He was elected president of the Medical Society of Nova Scotia in 1863 and, while a Member of Parliament, became the first president of the Canadian Medical Association (1867–70). While sitting for a term in opposition (1874–78), he returned to medicine, practising until his party returned to government, at which point his medical career dwindled.

Tupper is commemorated by the Canadian Medical Association through the Sir Charles Tupper Award for Political Action, which is awarded to a doctor “who has demonstrated leadership, commitment and dedication in advancing the goals and policies of the CMA through grassroots advocacy.”

Confederation

As premier, Charles Tupper championed both Maritime and British North American union, which he did not feel were incompatible goals. He was a delegate at the Charlottetown, Québec and London Conferences but was unable to win approval for the Québec Resolutions in the Nova Scotia Assembly. He argued that joining Canada would strengthen Nova Scotia’s commercial sector and provide the colony with greater influence in Canada and the broader British Empire.

“What is a British-American, but a man regarded as a mere dependent upon an empire which, however great and glorious, does not recognize him as entitled to any voice in her Senate, or possessing any interests worthy of imperial regard,” he said in a landmark speech in 1860. “British America, stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific, would in a few years exhibit to the world a great and powerful organization.”

Backed by a booming provincial economy, Tupper expanded the rail network and enhanced education with the Free School Act, which created state-subsidized public schools. The outbreak of the American Civil War convinced him that joining a wider Canadian union was crucial to Nova Scotia’s safe future.

In 1864, Tupper focused on what seemed to be the more achievable goal of Maritime union — a possible stepping stone to a national federation. Canadian representatives joined Tupper at the Charlottetown Conference and talk quickly turned from Maritime union to Confederation. Tupper envisioned a centralized federal union that would reserve significant independence for the provinces. After much political work, and in the teeth of strong opposition from Joseph Howe, a strong anti-Confederation voice, Tupper won a vote in favour of union from the Nova Scotia Assembly in 1866.

See also Nova Scotia and Confederation.

Post-Confederation Politics

Charles Tupper left provincial politics in 1867 and won a federal seat as the only supporter of Confederation from Nova Scotia. Although his claim for a Cabinet post was strong, he stood aside to allow others from Nova Scotia to enter the ministry — a strategy used to soften anti-Confederation sentiment in the province. Tupper also helped bring about the "better terms" settlement with Joseph Howe. The agreement between Tupper and Howe stipulated that the two men would work together to protect Nova Scotia’s interests in Parliament in exchange for Howe’s support for Confederation. As a result, Howe was given a position in Cabinet in 1870, and Tupper began his long ministerial career. Tupper served successively as president of the Privy Council (1870–72), minister of inland revenue (1872–73) and minister of customs (1873) in the first government of Sir John A. Macdonald.

When the Conservatives returned to office following the Pacific Scandal, Tupper served as minister of public works (1878–79) and minister of railways and canals (1879–84). During this time, construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway was nearing completion. Tupper became high commissioner to the United Kingdom in 1883, but returned to Ottawa to serve as minister of finance (1887–88). Resuming his duties in London, he became known as an outspoken advocate of imperial federation with the United Kingdom. Sir John A. Macdonald was not pleased with Tupper's views, but Tupper’s political standing allowed him immunity from censure.

In January 1896, Tupper was called back to Ottawa to serve as secretary of state in the failing government of Sir Mackenzie Bowell. Having been passed over for the party leadership in favour of John Abbott, John Thompson and Bowell, Tupper finally became prime minister on 1 May 1896. In a desperate attempt to stave off defeat in the House, Tupper and his colleagues introduced remedial legislation to protect the educational rights of the French-speaking minority in Manitoba (see Manitoba Schools Question). The bill was blocked in the Commons.

Tupper and the Conservatives suffered a stunning general election defeat that June, as Québec's returns were decisive. He resigned on 8 July, having served only 10 weeks as prime minister, the shortest tenure in Canadian history. He continued in Parliament as Leader of the Opposition but was defeated in the election of 1900.

Life after Politics

After retirement, Sir Charles Tupper was appointed to the British Privy Council in 1907 and served on the committee of the British Empire. His wife, Frances, died in 1912, closing their 65-year marriage. Their son, Charles Hibbert Tupper, entered politics and served as a Cabinet minister for several prime ministers.

Tupper lived in Vancouver before moving to live with one of his daughters in England in 1913, where he died of heart failure on 30 October 1915. His remains were returned to Canada and buried in Halifax.

Legacy

Sir Charles Tupper was a decisive figure in Canadian political life. His unlikely defeat of Joseph Howe in his first election gave him the platform he would eventually use to bring Nova Scotia into Confederation in 1867. As one of Sir John A. Macdonald's principal lieutenants, he had a defined capacity for administration as well as a reputation for parliamentary bluff and bullying. When he died in 1915, he was the last surviving Father of Confederation.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom