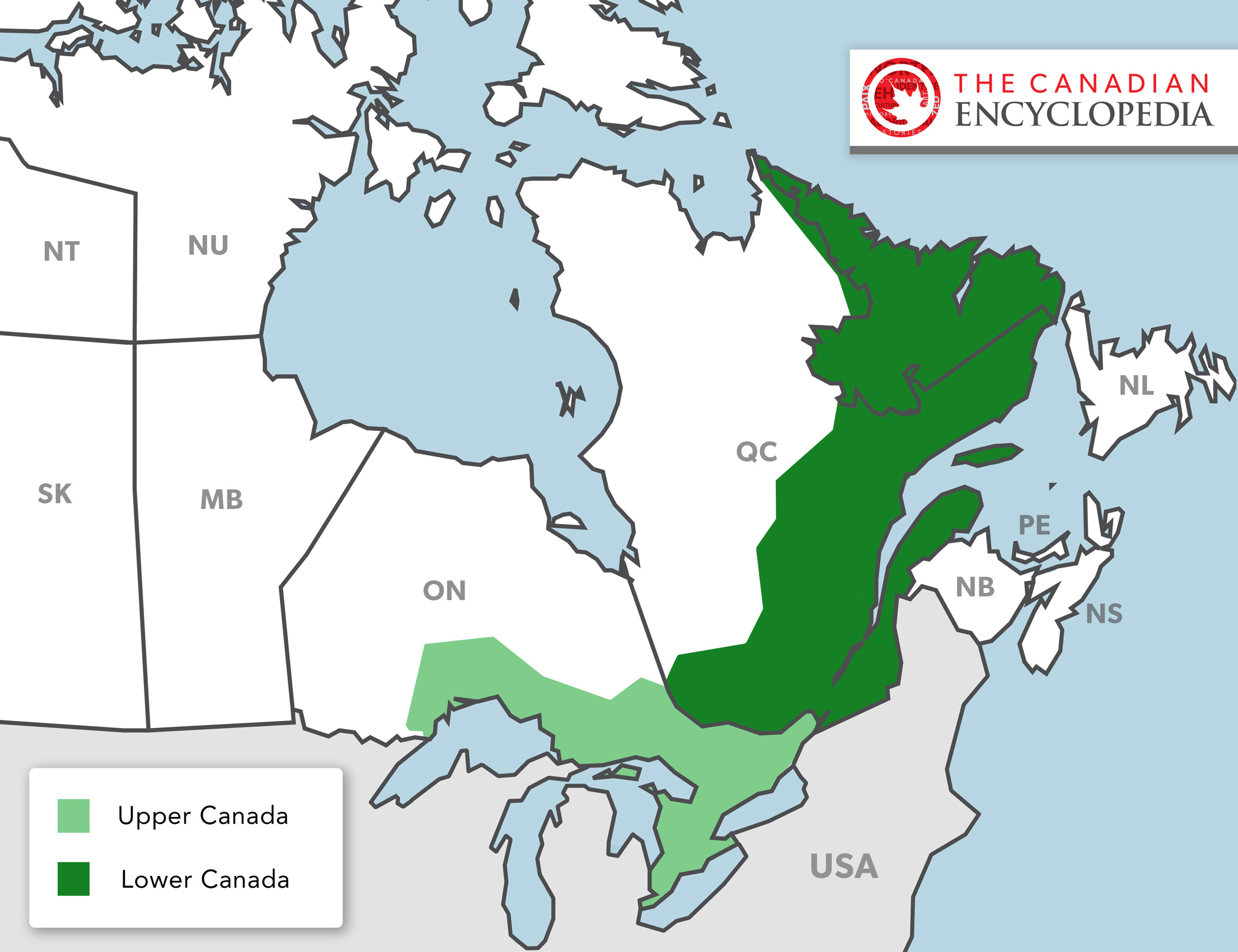

At the end of the Seven Years’ War (1756–63), Great Britain set out to organize the North American territories surrendered by France in the Treaty of Paris, 1763. By the Royal Proclamation of 1763, the Province of Quebec was created out of the inhabited portion of New France. The boundaries took on a rectangular shape on each side of the St. Lawrence River, and stretching from Lake Nipissing and the 45th parallel to the Saint John River and Ile d'Anticosti. These boundaries were modified by the Quebec Act of 1774 to include the fishing zone off Labrador and the Lower North Shore, and the fur trade area between the Ohio and Mississippi rivers and the Great Lakes. The Treaty of Paris, 1783 pushed the boundary farther north. With the Constitutional Act, 1791, Britain divided the Province of Quebec into Upper Canada (the predecessor of modern-day Ontario) and Lower Canada (whose geographical boundaries comprised the southern portion of present-day Quebec).

Following the Seven Years’ War and the Treaty of Paris 1763, Britain created a colony called the Province of Quebec.

The Fur Trade

Many of the province's inhabitants were, or had been, employed by fur-trade companies and merchants. As such, their geographic universe was not limited to these official boundaries; in reality, it stretched westward to include what fur traders referred to as the pays d’en haut (French for "up country" or "upper country") and the North-West, the source of the colony's main export (see Fur Trade Routes). The fur trade had been virtually destroyed during the war and then hobbled first by the revolt of Odawa chief Obwandiyag (Pontiac) and later by the restrictions imposed by British authorities. It took nearly a decade to revive the trade, but the traders eventually occupied the previous French territory. Then, following the example set by Peter Pond, they explored and exploited new areas.

Did you know? In New France, pays d'en haut was an expression used to refer to what is now northwest Quebec (except for the King's Posts), most of Ontario, the area west of the Mississippi and south of the Great Lakes and beyond to the Canadian prairies. This was the area where voyageurs travelled to trade furs.

By 1789, when explorer Alexander MacKenzie descended the large river that would later bear his name on European maps (see Mackenzie River) to the Arctic Ocean, the entire North-West, from Lake Superior to the Rockies, had been linked to the Province of Quebec through the activities of the voyageurs and fur traders. Between 1763-91 Montreal merchants drained off most of the furs from the southwest. Competition from New York and Albany was gradually eliminated by the 1768 decision to return to the colonies the regulation of the fur trade and by the 1774 annexation of the Ohio territory to the province. That region had ties with Montreal even after the 1783 treaty, since Britain retained the posts south of the Great Lakes until 1796 (see Jay’s Treaty).

Although the fur trade was vital for the province and its commerce with Britain, it was not the main domestic economic activity. Agriculture, especially the growing and preparation of wheat products, occupied the largest number of people and supplied the local market. Surpluses increasingly allowed food to be exported to the West Indies and Britain. Industrial production at the artisan level supplied domestic needs and the smaller needs of the fur trade.

Population Growth after the American Revolutionary War

In the late 18th century, a high birth rate led the population to more than double, from nearly 70 000 in 1775 to nearly 144 000 in 1784 and over 161 000 in 1790.

Migration from Britain or France played little part in this growth. About 3000 people left the St. Lawrence Valley after the Conquest of New France, and the expected British immigration did not take place. The number of "old subjects" was very small - some 500 in 1766 and perhaps 2000 in 1780. Their number grew significantly only after the American Revolutionary War (1775–83) when Loyalists arrived in significant numbers; the 1784 census listed some 25 000. The Loyalists settled mainly in the southwestern part of the province, which later became Upper Canada [Ontario].

Tensions Between English Administrators and Merchants in the Province of Quebec

The British, many of whom were merchants and officials, held influence and status that was disproportionate to their smaller numbers in relation to the French. The governors, James Murray, Guy Carleton and Frederick Haldimand, were responsible for the province. They and their entourages (which often included francophones) therefore held social as well as political power. The merchants, with the advantage of credit in London, soon controlled commercial relations with Great Britain. At first supported by the military authorities and helped by francophone voyageurs, they acquired the lion's share of the fur trade in less than two decades. They established the North West Company, which took an increasingly larger share of the trade. By 1790, it was the most powerful fur-trade organization in the Province of Quebec.

The administrators and merchants often failed to see eye to eye. The merchants even managed to have Murray, the first governor, recalled. The dispute with Murray centered on the application of British law and the creation of an Assembly, as provided for in the Proclamation of 1763. The merchants felt that these institutions were essential to the anglicizing of the colony and the protection of British interests. They perceived and defined these interests as those of Britons residing in the colony.

But both Murray and Carleton defined British interests as the interests of the British Crown, and they therefore felt that their main task was to avoid any threat to the Crown's possession of the colony. Given the style of government adopted during the period of military occupation (1760-63), the lack of British immigration and the growing unrest in the Thirteen Colonies, the governor had no choice but to try to win over the majority of the population. Major portions of the Proclamation were set aside and "new subjects" were appointed to official positions.

The Quebec Act, 1774

In 1774, Carleton, who was determined to preserve a military base of operations in North America, obtained the passage of the Quebec Act. (See The Quebec Act, 1774 (Plain Language Summary).) It fell far short of pleasing the merchants, who wanted an Assembly, even though it strengthened their monopoly on the fur trade to the south. The governor hoped the Act would win the support of the francophone elite. Murray had already gained the collaboration of the Roman Catholic clergy (see Catholicism in Canada). The death of Bishop Henri-Marie Dubreil de Pontbriand in 1760 had left the church without a bishop to run its affairs and ordain new priests; moreover, funds were desperately short and war-destroyed buildings had to be replaced. Murray therefore made himself the champion of the church and was instrumental in bringing about the 1766 consecration in France of Jean-Olivier Briand as the new bishop of Quebec.

The Quebec Act allowed the free practice of the Catholic faith, re-established the Coutume de Paris in civil matters (see Civil Code). Though English criminal law was retained, the Act restored French civil law. Among other things, this meant that the Roman Catholic Church could now legally collect tithes. The seigneurial system was also re-established. While the seigneurs and church officials were undoubtedly happy, French-speaking inhabitants were less pleased about having to pay seigneurial dues and taxes.

Did you know? In present-day Canada, only Quebec has a Civil Code. Unlike an Administrative Code, Criminal Code or Code of Civil Procedure, a Civil Code expounds only on matters of private law.

Under the Quebec Act, a council was created and the abolition of the Test Oath allowed Catholics to enter public office. But these conciliatory measures failed to have the desired effect. The habitants showed little enthusiasm for British interests, especially during the American invasion of 1775-76. Nevertheless, for various reasons, they also failed to side with the revolutionaries. Ultimately, Carleton's strategy had partial success: the province remained British.

The Constitutional Act, 1791

The sociopolitical structure created by the Quebec Act failed to survive the consequences of war. It was upset by the arrival of the Loyalists, and this increase in British population greatly strengthened the merchants' position and intensified their

conflict with the governor. The British authorities asked Carleton (now Lord Dorchester) to suggest a solution to the problem. To satisfy, at least partially, the merchants and the Loyalists without angering the francophones, in 1791 London produced

a revised Quebec Act and a new constitution, which included the creation of a House of Assembly (see Constitutional Act 1791). The new provinces of Lower

and Upper Canada were created, with Lower Canada retaining many of the institutional forms of the Province of Quebec.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom