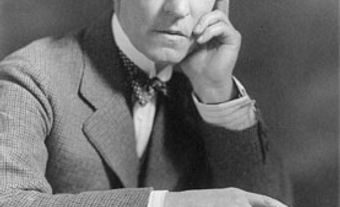

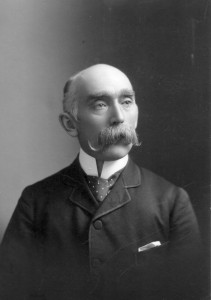

Peter Henderson Bryce, physician, public health official (born 17 August 1853 in Mount Pleasant, Canada West; died 15 January 1932 at sea). Dr. Peter Henderson Bryce was a pioneer of public health and sanitation policy in Canada. He is most remembered for his efforts to improve the health and living conditions of Indigenous people. His Report on the Indian Schools of Manitoba and the Northwest Territories exposed the unsanitary conditions of residential schools in the Prairie provinces. It also prompted national calls for residential school reform.

Click here for definitions of key terms used in this article.

Early Life and Education

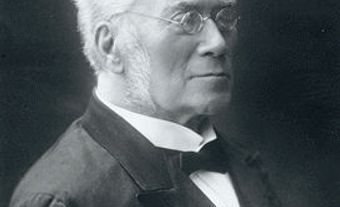

Peter Henderson Bryce’s father, George Bryce Sr., was prominent within the local Presbyterian community. He served as Justice of the Peace for Brant County in Upper Canada (now Ontario). George Sr. and his wife, Catherine, encouraged their son’s education. Peter graduated from Upper Canada College. He then attended the University of Toronto, where he earned his BA, MA and MB (Bachelor of Medicine).

Bryce continued his advanced medical education in Europe. After a brief stint as a professor at the University of Guelph, he left Canada in 1880 to study in Edinburgh and Paris. In Paris, he studied neurology at the renowned Salpêtrière hospital. He returned to Canada in 1881 as a fellow of Edinburgh’s Royal College of Physicians and a member of the Sanitary Institute of Great Britain. He settled once again in Guelph, where he opened a general medical practice. In 1888, he completed his medical training, earning his MD.

Career

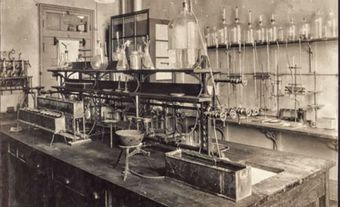

In 1882, Peter Henderson Bryce accepted a patronage position as the secretary of Sir Oliver Mowat’s new Provincial Board of Health of Ontario. The two men were instrumental in drafting Ontario’s 1884 Public Health Act. In 1887, Bryce became the Board of Health’s chief officer. He was an early advocate of preventive medicine and public sanitation. He proposed pioneering measures including popular education on personal hygiene. Bryce also enacted policies to prevent the spread of disease. These policies included stricter government control of public water and food supplies, as well as the proper disposal of sewage. Like physicians in Europe and the United States, Bryce also began collecting detailed statistics about the health of the public. Bryce’s advocacy for sanitation and preventive medicine went beyond his role in the Ontario government. He was an active member of the Canadian Association for the Prevention of Tuberculosis. In 1900, he became the first Canadian president of the American Public Health Association.

In 1904, Bryce was appointed chief medical officer of the federal Departments of the Interior and Indian Affairs. In this role, he began to publicly challenge the common belief among White Canadians that people of other ethnicities had poor moral and physical health because they were inferior (see Racism). Instead, he argued that it was actually poor immigrants from Great Britain who posed a greater threat to the moral and physical purity of Canadian society. As chief medical officer, Bryce oversaw the medical inspection of immigrants to Canada. His personal views on race and poverty therefore informed the development of immigration policy in the early 20th century. Bryce believed that social inequality could be overcome through social reform, including health promotion. In many ways, these views reflected the Social Gospel movement of his time.

Report on Residential Schools

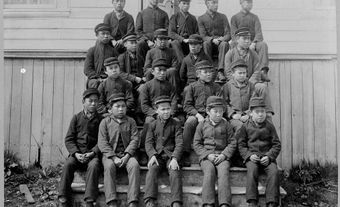

Moving to the federal civil service allowed Peter Henderson Bryce to apply his public health policies on a much larger scale. As chief medical officer of the Department of Indian Affairs, he began the collection of vital statistics for Indigenous people across the country. He also recommended setting up temporary hospitals on or near reserves to combat the alarmingly high rate of tuberculosis deaths. Indigenous people were dying of tuberculosis at a rate almost 20 times higher than that of non-Indigenous Canadians.

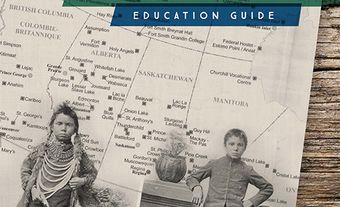

Bryce also began to push for better sanitation in residential schools. In 1907, he submitted his Report on the Indian Schools of Manitoba and the Northwest Territories. The report highlighted the staggering death rates at the schools. At one institution, the File Hills Colony residential school, Bryce found that 69 per cent of all alumni had died, almost all of them from tuberculosis. Bryce concluded that these deaths resulted from the poor conditions and lack of sanitation within the schools. His report made it clear that the federal government was directly responsible for these conditions.

The Department of Indian Affairs did not publish Bryce’s report. However, details from Bryce’s report were published by journalists, prompting calls for reform from across the country. Despite this public outcry, the residential schools were not closed. Bryce’s recommendations were largely ignored. Indigenous children continued to die of tuberculosis and other diseases at alarming rates. (See also Health of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.)

Later Life

Peter Henderson Bryce retired from the civil service in 1921. For the better part of two decades, he had tried to improve the living conditions of Indigenous people in Canada, with little success. He published The Story of a National Crime in 1922, a pamphlet that expressed his anger at the government’s inaction on this issue.

Bryce died at sea in 1932, at the age of 79, on his way to the West Indies. He was buried in Beechwood Cemetery in Ottawa.

Legacy

In 2015, a historical plaque was erected near Peter Henderson Bryce’s grave to commemorate his work in public health and efforts to address the conditions of residential schools. In 2024, he was named a Person of National Historic Significance by the Government of Canada.

Key Terms

Physician – A person trained and licensed to practise medicine (especially non-surgical diagnosis and treatment).

Preventive medicine – A branch of medicine focused on ways to prevent disease (e.g., through sanitation and education).

Residential schools – Government-sponsored religious schools that were established to assimilate Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian culture.

Sanitation – Systems and practices that promote health and prevent disease (e.g., sewage and waste disposal).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom