Background

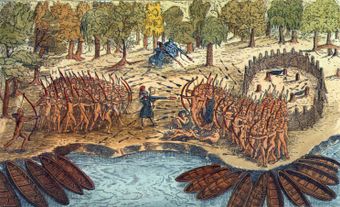

The century of warfare between the French and the Five Nations Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) was marked by a series of military expeditions and guerrilla raids. It was initiated by Samuel de Champlain in 1609. He joined a war party of Algonquin and Huron-Wendat against the Mohawk of the Lake Champlain region. He thus inserted the French into the pre-existing web of alliances and enemies that characterized North American Indigenous conflict at the time. He did so in the interests of strengthening New France’s position in the fur trade.

Following this, there were indecisive conflicts with the Haudenosaunee under governors Daniel de Rémy de Courcelle in 1665, Joseph-Antoine Le Febvre de La Barre in 1684 and Marquis de Denonville in 1687. It was not until 1696 that Governor Frontenac was able to stop the Haudenosaunee raids on New France. He also destroyed the villages and food supplies of the Onondaga and Oneida. This greatly weakened the Haudenosaunee and motivated them to negotiate with the French.

Negotiations Begin

Following Frontenac’s death in November 1698, Louis-Hector de Callière was promoted from governor of Montreal. He became governor of all New France in the spring of 1699 and began looking for ways to end the wars. In July 1700, delegates from four of the Haudenosaunee nations (the Mohawk were absent) met with Governor de Callière to begin peace talks. A meeting of all the nations, including the five nations of the Haudenosaunee and all other nations allied with the French, was scheduled for the following summer in Montreal.

Thirty-nine nations sent a total of 1,300 delegates to discuss terms of collective action. (The population of Montreal at the time was about 1,200.) They came from as far as the Maritimes in the east and present-day Illinois in the west. The negotiations took several weeks and concluded on 4 August 1701. Through the Haudenosaunee condolence ceremony — the exchange of gifts and prisoners and the solemn “signing” of accords — the several nations agreed to remain at peace with each other. Governor de Callière had wampum belts commissioned for each Indigenous nation to commemorate the treaty.

In the peace treaty of 1701, pictograms represent the signatories of the various nations. For example, figure 1, a wading bird, represents Ouentsiouan of the Onondaga nation.

Terms and Significance

The Iroquois League pledged to allow French settlement at Detroit and to remain neutral in the event of a war between England and France. In exchange, the Haudenosaunee were permitted to trade freely and to obtain goods from the French at a reduced cost. All agreed that the governor general of New France would mediate disputes among them. This recognized a special kinship relationship with the French.

The Montreal accord brought peace that lasted until the British conquest of New France in 1760. The agreement assured New France superiority in dealing with issues related to the region’s First Nations. It also gave the French the freedom to expand militarily over the next half century. However, it also undermined the effectiveness of the Covenant Chain —the system of alliances between the Haudenosaunee and the Thirteen American Colonies. This led to worsening relations between them.

Anniversary Commemorations

To mark the 300th anniversary of the peace treaty in 2001, the Pointe-à-Callière museum of anthropology in Montreal hosted an exhibition of artifacts related to the accord, including the original manuscript. The City of Montreal also named part of Place d’Youville, Place de la Grande-Paix-de-Montréal. An obelisk marks the location where the treaty was signed.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom