Its development can be broken into the following periods:

(1867-1913) Immigration and Industrialization

(1914-1918) War, Victory and Autonomy

(1919-1938) Labour Unrest and the Great Depression

(1945-1971) Cold War and the Québec Agenda

(1972-1980) The Inflation Curse and Regional Divides

(1981-1992) The Constitution Decade

(1993-2005) Liberal Hegemony — and Collapse

(1867-1913) Immigration and Industrialization

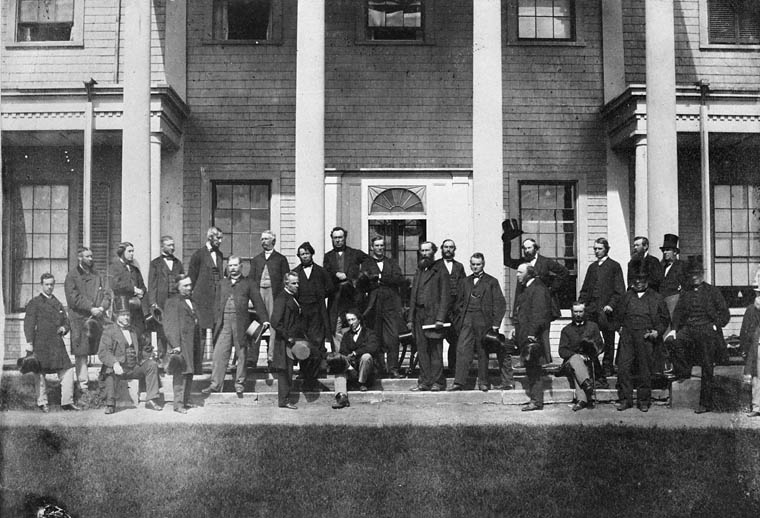

In 1867, the new state—beginning with Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Québec and Ontario—expanded extraordinarily in less than a decade, stretching from sea to sea. Rupert's Land, from northwestern Québec to the Rockies and north to the Arctic, was purchased from the Hudson's Bay Company in 1869-70. From it were carved Manitoba and the Northwest Territories in 1870. A year later, British Columbia entered Confederation on the promise of a transcontinental railway. Prince Edward Island was added in 1873. Alberta and Saskatchewan won provincial status in 1905, after mass immigration at the turn of the century began to fill the vast Prairie West (see Territorial Evolution).

Sir John A. Macdonald's Dream

Under the leadership of the first federal prime minister, Sir John A. Macdonald, and his chief Québec colleague, Sir George-Étienne Cartier, the Conservative Party — almost permanently in office until 1896 — committed itself to the expansionist National Policy. It showered the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) with cash and land grants, achieving its completion in 1885. The government erected a high, protective customs-tariff wall to shield developing Canadian industrialism from foreign, especially American, competition. The other objective, mass settlement of the west, largely eluded them, but success came to their Liberal successors after 1896. Throughout this period there were detractors who resented the CPR's monopoly or felt — as did many in the West and on the East Coast — that the high tariff principally benefited central Canada. Yet the tariff had support in some parts of the Maritimes.

Rise of Radical Nationalism

The earliest post-Confederation years saw the flowering of two significant movements of intense nationalism. In English Canada the very majesty of the great land, the ambitions and idealism of the educated young and an understanding that absorption by the United States threatened a too-timid Canada, all spurred the growth of the Canada First movement in literature and politics — promoting an Anglo-Protestant race and culture in Canada, and fierce independence from the U.S.. The Canada Firsters' nationalist-imperialist vision of grandeur for their country did not admit the distinctiveness of the French, Roman Catholic culture that was a part of the nation's makeup.

The group's counterparts in Québec, the ultramontanes, believed in papal supremacy, in the Roman Catholic Church and in the clerical domination of society. Their movement had its roots in the European counter-revolution of the mid-19th century. It found fertile soil in a French Canada resentful at re-conquest by the British after the abortive Rebellions of 1837, and distrustful of North American secular democracy. The coming of responsible government in Nova Scotia and in the Province of Canada by 1850, and of federalism in the new Confederation, encouraged these clericalist zealots to try to "purify" Québec politics and society on conservative Catholic lines. The bulwark of Catholicism and of Canadien distinctiveness was to be the French language. Confederation was a necessary evil, the least objectionable non-Catholic association for their cultural nation. Separatism was dismissed as unthinkable and impractical, in the face of the threats posed by American secularism and materialism. But a pan-Canadian national vision was no part of their view of the future.

These two extreme, antithetical views of Canada could co-exist so long as the English-speaking and French-speaking populations remained separate, and little social or economic interchange was required. But as the peopling of border and frontier areas in Ontario and the West continued, and as the industrialization of Québec accelerated, conflicts multiplied. The harsh ultramontane attacks on liberal Catholicism and freedom of thought in Québec alarmed Protestant opinion in English Canada, while the lack of toleration of Catholic minority school rights and of the French language outside Québec infuriated the Québecois (see Manitoba Schools Question). Increasing, social and economic domination of Québec by the Anglophone Canadian business class exacerbated the feeling.

Prosperity and Growth

Economic growth was slow at first and varied widely from region to region. Industrial development steadily benefited southern Ontario, the upper St Lawrence River Valley and parts of the Maritimes. But rural Ontario west of Toronto and most of backcountry Québec steadily lost population as modern farming techniques, soil depletion and steep increases in American agricultural tariffs permitted fewer farmers to make their living on the land. Emigration from the Maritimes was prompted by a decline of the traditional forestry and shipbuilding industries. The Maritime economy was also hurt by the withering of bilateral trading links with the New England states, due in part to Ottawa's protectionist National Policy. Nationwide, from the 1870s through the 1890s, 1.5 million Canadians left the country, mostly for the U.S. (see Population).

Fortunately, prosperous times came at last, with the rising tide of immigration—just over 50,000 immigrants arrived in 1901, jumping to eight times that figure 12 years later. A country of 4.8 million in 1891 swelled to 7.2 million in 1911. The prairie "wheat boom" was a major component of the national success. Wheat production shot up from 8 million bushels in 1896 to 231 million bushels in 1911. Prairie population rose as dramatically, necessitating the creation of the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan in 1905 and the completion of two new cross-Canada railways — the Grand Trunk Pacific and the Canadian Northern. Western cities, especially Winnipeg and Vancouver, experienced breakaway expansion as trading and shipping centres. Nearly 30 per cent of the new immigration went to Ontario, with Toronto taking the lion's share for its factories, stockyards, stores and construction gangs. Both Toronto and Montréal more than doubled their population in the 20 years before 1914.

Social Change, Government Expansion

As Canada increasingly became an urban and industrial society, the self-help and family-related social-assistance practices of earlier times were outmoded. The vigorous Social Gospel movement among Protestants and the multiplication of social-assistance activities by Roman Catholic orders and agencies constituted impressive responses, however inadequate. Governments, especially at the provincial level, expanded their roles in education, labour and welfare. An increasingly significant presence in social reform work was that of women, who also began to exert pressure for the vote.

Through immigration, Canada was becoming a multicultural society, at least in the West and in the major, growing industrial cities. Roughly one-third of the immigrants came from non-English-speaking Europe. Ukrainians, Russian Jews, Poles, Germans, Italians, Dutch and Scandinavians were the principal groups. In BC there were small but increasing populations of Chinese, Japanese and East Indians. There were growing signs of unease among both English and French Canadians about the presence of so many "strangers," but the old social makeup of Canada had been altered forever.

Resistance in the West

Meanwhile, there was a reduction in the extent of territories controlled by First Nations, and in their degree of self-determination. In the Arctic, the Inuit remained largely undisturbed, but most western First Nations and Métis people lost their way of life as white settlement, farming and railroads encroached on much of their hunting lands. In 1869-70 in the Red River region, and in 1885 at Batoche in Saskatchewan, there were unsuccessful armed Métis resistance movements led by Louis Riel (see Red River Resistance; North-West Resistance). During the second uprising some First Nations groups were directly involved. Otherwise the settlement of the West was generally peaceful — land was obtained in exchange for treaty and reservation rights for First Nations, and through land grants to the Métis. Order was kept by the new, North-West Mounted Police.

Sir Wilfrid Laurier

In 1896 the prime ministership of Canada passed to the Québecois Liberal Roman Catholic Sir Wilfrid Laurier. He presided over the greatest prosperity Canadians had yet seen, but his 15 years of power were bedeviled and then ended by difficult problems in Canada's relationships with Britain and the U.S.. During Laurier's tenure, Britain's interest in a united and powerful empire intensified. Many English Canadians were swept up in Imperial emotion and Canadian nationalist ambition, and called for an enlarged imperial role for Canada. They forced the Laurier government to send troops to aid Britain in the South African War, 1899-1902, and to begin a Canadian navy in 1910. In the same spirit came a massive Canadian contribution of men and money to the British cause in the cataclysm of the First World War.

By then the Laurier administration had been defeated, in part because too many English Canadian imperialists thought it was "not British enough," and because the growing nationaliste movement in Québec, led by Henri Bourassa, was sure that it was "too British," and would involve young Québec boys in foreign wars of no particular concern to Canada. But the chief cause of Laurier's defeat in the general election of 1911 was his proposed reciprocity or free trade agreement with the U.S., which would have led to the reciprocal removal or lowering of duties on the so-called "natural" products of farms, forests and fisheries.

The captains of Canadian finance, manufacturing and transport excited the strong Canadian suspicions of American economic intentions and, with their support, the Conservative Opposition under Robert Borden convinced the electorate that Canada's separate national economy and imperial trading possibilities were about to be thrown away for economic, and possibly political, absorption by the U.S..

(1914-1918) War, Victory and Autonomy

Although economic fears helped propel Borden into power, his government was soon preoccupied not with trade or the economy, but overseas war. Europe's great powers had embarked on a conflict like the world had never seen, and as Britain was drawn into the First World War, so automatically was Canada. There was extraordinary voluntary participation on land, at sea and in the air by Canadians (see Wartime Home Front). But in 1917 the country was split severely over the question of conscription, or compulsory military service. The question arose as a result of a severe shortage of Allied manpower on the Western Front in Europe. The subsequent election of a pro-conscription Union government of English Canadian Liberals and Conservatives under Borden, over Laurier's Liberal anti-conscriptionist rump — its support drawn largely from French Canadians, non-British immigrants and radical labour elements — dramatized the national split.

Canada Emerges on World Stage

Yet the war also had a positive impact on Canada. Industrial productivity and efficiency had been stimulated. Canada won a new international status, as a separate signatory to the Treaty of Versailles, and as a charter member of the new League of Nations. And the place of women in Canadian life had been upgraded dramatically. They had received the vote federally, primarily for partisan political reasons. But their stellar war service, often in difficult and dirty jobs hitherto thought unfeminine, had won them a measure of respect; they had also gained a taste for fuller participation in the work world. Canadian men and women, on a much broadened social scale, had been drawn into the mainstream of a western consumer civilization.

The war itself ushered in slaughter on an industrial scale, and Canada paid a high price. Among the roughly 630,000 who served in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, 425,000 were sent overseas — witnessing the horrors of battlefields at Ypres, Vimy, Passchendaele and elsewhere. By the end, more than 234,000 Canadians had been killed or wounded in the war.

By 1919, the attempted shift to a peacetime economy was soon clouded by high inflation and unemployment, as well as disastrously low world grain prices. Labour unrest increased radically, farmer protests toppled governments in the West and Ontario, and the economy of the Maritimes collapsed. Resentment over conscription remained intense in Québec. The early national period of Canadian innocence was over.

(1919-1938) Labour Unrest and the Great Depression

Canada's population between the world wars rose from 8 to 11 million; the urban population increased at a more rapid rate from 4 to 6 million. The First World War created expectations for a brave new Canada, but peace brought disillusionment and social unrest. Enlistment in the armed forces and the expansion of the munitions industry had created a manpower shortage during the war, which in turn had facilitated collective bargaining by industrial workers. There had been no dearth of grievances about wages or working conditions, but the demands of patriotism had usually restrained the militant. Trade-union membership grew from a low of 143,000 in 1915 to a high of 379,000 in 1919, and with the end of the war the demands for social justice were no longer held in check. Even unorganized workers expected peace to bring them substantial economic benefits.

Labour Troubles

Employers had a different perspective. Munitions contracts were abruptly cancelled and factories had to retool for domestic production. The returning veterans added to the disruption by flooding the labour market. Some entrepreneurs and political leaders were also disturbed by the implications of the 1917 Russian Revolution and were quick to interpret labour demands, especially when couched in militant terms, as a threat to the established order. The result was the bitterest industrial strife in Canadian history. In 1919, with a labour force of some 3 million, almost 4 million working days were lost because of strikes and lockouts. The best-known of that year, the Winnipeg General Strike, has a symbolic significance: it began as a strike by construction unions for union recognition and higher wages, but quickly broadened to a sympathy strike by organized and unorganized workers in the city. Businessmen and politicians at all levels of government feared a revolution. Ten strike leaders were arrested and a demonstration was broken up by mounted policemen. After five weeks the strikers accepted a token settlement, and the strike was effectively broken.

Industrial strife continued, with average annual losses of a million working days until the mid-1920s. By then the postwar recession had been reversed and wages and employment levels were at record highs for the rest of the decade. Some labour militants turned from the economic to the political sphere, becoming successful early in the decade in provincial elections in Nova Scotia, Ontario and the four western provinces, and J.S. Woodsworth, the pioneering preacher-turned socialist politician, was elected in north Winnipeg in the 1921 federal election.

Mackenzie King and the New Politics

The war also left a heritage of grievances in rural society. Rural depopulation had accelerated during the war, but the farmers' frustration was directed against the Union government of Sir Robert Borden, which had first promised exemptions and then conscripted farm workers. A sudden drop in prices for farm produce increased their bitterness. In postwar provincial elections, farmers' parties formed governments in Ontario, Manitoba and Alberta, and in the federal election of 1921, won by William Lyon Mackenzie King's Liberals, the new Progressive Party captured an astonishing 65 seats on a platform of lower tariffs, lower freight rates and government marketing of farm products.

These social protests declined by the end of the decade. Industrial expansion, financed largely by American investment, provided work in the automotive industry, in pulp and paper and in mining. Farm incomes rose after the postwar recession, reaching a high of over $1 billion in 1927. The political system also offered some accommodation. Most provincial governments introduced minimum wages shortly after the war, and the federal government reduced tariffs and freight rates and introduced old-age pensions. By the end of the decade the impetus for social change had dissipated. Even wartime prohibition experiments had given way to the lucrative selling of liquor by provincial boards.

Great Depression

But the good times of the late 1920s didn't last. In fact, they masked brewing trouble in financial markets, and the coming trauma of the Great Depression. For wheat farmers it began in 1930 when the price of wheat dropped below $1 a bushel. Three years later it was down to about 40 cents and the price of other farm products had dropped as precipitously. Prairie farmers were the hardest hit because they relied on cash crops, and because the depressed prices happened to coincide with a cyclical period of drought, which brought crop failures and a lack of feed for livestock. Cash income for prairie farmers dropped from a high of $620 million in 1928 to a low of $177 million in 1931 and did not reach $300 million until 1939.

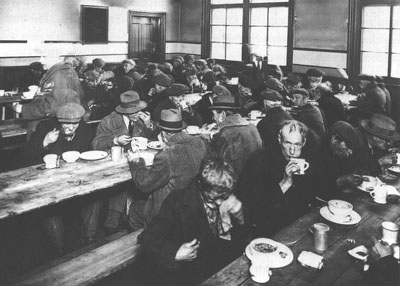

Disaster also struck many industrial workers who lost their jobs. Unemployment statistics are not reliable partly because there was no unemployment insurance and so no bookkeeping records, but it is estimated that unemployment rose from three per cent of the labour force in 1929 to 20 per cent in 1933. It was still 11 per cent by the end of the decade. Even these figures are misleading: the labour force included only those who were employed or looking for work, excluding most women. Those identified as unemployed were often the only breadwinners in the family.

Role of Government Evolves

Voters turned to governments for an economic security that the system could not provide. Most governments were slow or unable to respond and were replaced by others at the first opportunity. King's Liberals, elected in 1926 after a brief period of Conservative rule, were again rejected in 1930, this time in favour of a Conservative government under R.B. Bennett. New political parties arose across the ideological spectrum, contesting the 1935 federal election — the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), Social Credit and the short-lived Reconstruction Party — with promises to regulate credit and business.

Even Bennett's Conservatives promised improvements (see Bennett's New Deal), and Mackenzie King and the Liberals, who won the election, spoke vaguely of reform. At the provincial level, the Union Nationale was elected in Québec under Maurice Duplessis and Social Credit in Alberta under William Aberhart. Older parties in other provinces often turned to new and more dynamic leaders who promised active intervention on behalf of the less privileged.

Governments tried to provide emergency relief, but they too soon needed help. Prairie farmers needed relief in the form of food, fuel and clothing, but they also needed money for seed grain, livestock forage and machinery repairs. Neither municipal nor provincial governments could meet these demands for assistance; in the drought year of 1937 almost two-thirds of Saskatchewan's population required some relief. Other provinces had declining revenues but were not as close to bankruptcy, with the possible exception of Alberta. Inevitably, as the Depression continued, the federal government had to contribute to relief costs.

The role of governments changed, but not dramatically. Most governments would have preferred to provide jobs by undertaking major public-works projects, but with declining revenues and limited credit the cost of materials and equipment was prohibitive. Direct relief was cheaper in the short run. Governments did become more involved in the regulation of business: mortgages and interest payments were scaled down by legislation, and new regulatory institutions such as the Bank of Canada and the Canadian Wheat Board were established. The major expansion of the bureaucracy, however, would come only after the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939.

Trade-union activity revived with the beginning of industrial recovery: by 1937 trade-union membership was back to the 1919 level. Canadian auto workers and miners followed the American lead and formed industrial unions. Their effectiveness was limited by the opposition of Ontario Premier Mitchell Hepburn and Duplessis in Québec, and the significant gains, once again, would come only during the war.

A New Culture: Cars and Radio

During the 1920s and 1930s, two machines may have done more than the highs and lows of the business cycle to alter the Canadian way of life: the automobile and the radio. The 1920s were the decade of the car — in 1919 there was one car in Canada for every 40 people; 10 years later it was one car for every 10. The car created Canadian suburbs and altered the social patterns of the young.

In the 1930s it was the radio: there were half-a-million receiving sets in 1930 and over a million by 1939, bringing news and entertainment into most Canadian homes. The changes brought about by mass production and popular entertainment posed problems for Canadian identity. The tariff (see Protectionism) provided Canadian jobs by ensuring that cars and radios would be assembled in Canada. There was little concern at the time for one economic side effect: the expansion of U.S. manufacturing branch-plants. But there was concern for the broadcasting of American programs by Canadian radio stations. The result was the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, with French and English networks broadcasting a combination of Canadian and popular American programs. By 1939 Canadians looked to governments to provide cautious assistance in maintaining Canadian identity.

(1939-1945) Second World War

Before the outbreak of another world war, Canada played host to the first overseas visit by a reigning British (and Canadian) monarch. King George VI and Queen Elizabeth (later called the Queen Mother) spent one month crossing the country by train. In an age before television, it was a dazzling event, one of the greatest public spectacles in Canadian history. The royal couple was greeted by enormous crowds wherever they went in both French and English Canada, and the tour witnessed the first-ever royal walkabout — when the couple plunged into a crowd to shake hands at the National War Memorial in Ottawa. The underlying purpose of the visit was to rally support in North America for the coming Allied war against Nazi Germany, and it wasn't long before Canada was once again transforming itself into a warrior nation.

Sacrifice and Social Change

As the previous war had, the Second World War reinvigorated Canada's industrial base and elevated the role of women in the economy; women earned good incomes at jobs created by the huge demand for military materiel, and also vacated by men going to war. More than a million Canadians served full-time in the armed forces between 1939-1945, allowing Canada to play a critical role in the Battle of the Atlantic, the Allied bombing campaigns over Europe, the invasions of Italy and Normandy, and the subsequent liberation campaign in western Europe. More than 45,000 Canadians died fighting in Hong Kong, Dieppe, on the Atlantic and across Europe.

Canada's political landscape had been fundamentally changed by the First World War. During the Second, many predicted another transformation. In 1943 the socialist Commonwealth-Co-operative Federation (CCF) party, a product of 1930s political discontent, stood highest in new public opinion polls. It became the official Opposition in Ontario in 1943 and in 1944 won decisively in Saskatchewan. In Québec, Maurice Duplessis's Union Nationale recaptured power. Federally, Québec's Bloc populaire retaliated against conscription in 1944. Once again it seemed that the traditional Canadian party system would become a casualty of a European war.

Liberal Era Dawns in Ottawa

In the federal election of 11 June 1945 — held while thousands of veterans were just beginning to come home — Canadians returned the Liberal Party to office. Mackenzie King's majority was very small, but his survival is nevertheless remarkable: among Allied wartime leaders, only King and Stalin led their countries through both the war and the peacemaking.

In 1945, the Liberals added a new commitment to social welfare and Keynesian management of the economy (see Keynesian Economics). Liberal welfare policies — including family allowance begun in 1944, and unemployment insurance (see Employment Insurance), begun in 1940 — attracted many workers and farmers, and rebuffed the challenges from the CCF on the left and the Conservatives on the right. Although the national Liberals continued to enjoy support in all regions and from all economic groups, the CCF and Social Credit held power, respectively, in Saskatchewan and Alberta throughout the 1950s and into the 1960s, and Social Credit governed BC from 1952 to 1972.

(1945-1971) Cold War and the Québec Agenda

Some historians have attributed Liberal political success to the postwar period's unparalleled prosperity, and to consensus on foreign policy arising from Cold War fears — few objected when Canada joined the United Nations (UN) in 1945 or, four years later, signed the North Atlantic Treaty (NATO), and then followed this by sending troops to NATO bases in Europe in 1951. Canadians understood that the nation needed political stability, and a highly competent cabinet and bureaucracy, after depression and war.

Louis St. Laurent and Korea

The Korean War once again embroiled Canadian troops in overseas combat, this time as part of a UN-led coalition of 16 countries fighting the Communist forces of China and North Korea. Nearly 27,000 Canadian military personnel served in Korea between 1950-1953. Five hundred sixteen Canadians lost their lives, and about 1,200 more were wounded.

In 1954, Canada's prosperity, and the national consensus on Cold War issues and other foreign policy matters began to disappear. There was a sharp economic slump in 1954, followed by worries that Canada's postwar boom was too dependent upon (mainly American) foreign investment. The cabinet's competency obviously weakened in 1954 when three prominent ministers, Douglas Abbott, Lionel Chevrier and Brooke Claxton, resigned from the government of Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent. In 1956 the Pipeline Debate revealed apparent Liberal arrogance and political clumsiness. Western allies also became divided during the Suez Crisis when France, Britain and Israel attacked Egypt, and the U.S. and Canada did not support them. The Crisis put Canadian diplomat Lester Pearson on the world stage, as a pioneer of UN peacekeeping, as a means of defusing the conflict.

John Diefenbaker

On 10 June 1957 the Conservative Party ended the Liberals' long reign in Ottawa. Most significant in explaining the victory was the Conservatives' choice of John Diefenbaker as leader. He brought a flamboyance and a populist appeal that his predecessor, George Drew, completely lacked. He was also a western Canadian who understood and shared the area's grievances against Ottawa. Diefenbaker's brief first term saw taxes cut and pensions raised. The new government also took Canada into the North American Aerospace Defence (NORAD) agreement with the U.S., and two years later scrapped the Avro Arrow interceptor and purchased Bomarc missiles, effective only with nuclear warheads.

Seeking escape from the confines of a minority government, Diefenbaker called an election for 31 March 1958. Although the Liberals now had Lester Pearson as leader, Diefenbaker won 208 of 265 seats on the strength of his charisma, his "vision" of a new Canada and his policy of northern development. His support was well distributed, except in Newfoundland (which had become the 10th province in 1949).

No one had predicted the extent of the Conservative triumph, but that did not prevent many commentators at the time from forecasting a Conservative dynasty and a return to the two-party system. Today, historians and political scientists tend to consider the 1958 election as an aberration that neither reflected nor affected the fundamental character of Canadian politics. Yet closer scrutiny reveals a lasting imprint. Since 1958 Conservatives have commanded western Canadian federal politics, and Liberals have found western seats increasingly difficult to obtain. On the other hand, Conservatives, who won 50 seats in Québec in 1958, did not recover from Diefenbaker's failure to build upon his victory there for more than 25 years.

Provincial Political Change

The CCF and the Liberals began rebuilding almost immediately—the Liberals by appealing to urban Canadians and Francophones, and the CCF by strengthening its links with organized labour. Provincial bases were important in this reconstruction. Social Credit governments in Alberta and, to a much lesser extent, BC assisted the Liberals. Within five days in June 1960, the Liberals were elected in Québec and New Brunswick. In Québec, Jean Lesage modernized Québec liberal traditions and introduced the Quiet Revolution.

In Saskatchewan, the CCF made sacrifices for its federal counterpart. Long-time Saskatchewan Premier Tommy Douglas went to Ottawa to lead the CCF's heir, the New Democratic Party, whose formation was an attempt to create a closer link with the labour movement. Without Douglas, the NDP in Saskatchewan bravely introduced medicare in 1962 and, under the lash of a scare campaign, lost the next election to the Liberals. Medicare, however, proved successful and soon became a popular national program.

By 1962 Diefenbaker's 1958 "vision" of Canada had become a nightmare to some and a joke to others. There had been postwar peaks in unemployment, record budget deficits and, in May 1962, a devaluation of the dollar. But neither Pearson nor Douglas made much impact as national leaders before the election of 18 June 1962; the Conservatives stayed in power as a minority government. By early 1963 the cabinet began to bicker, members resigned ostensibly on the issue of Canadian defence policy, and finally the government collapsed. In a bitter 1963 election campaign Diefenbaker charged that the U.S., which had openly criticized his refusal to accept nuclear weapons on Canadian soil, was colluding with the Liberals to defeat him. The Liberals brushed off the attack and excoriated Diefenbaker for alleged incompetence. On 8 April 1963, the Liberals won a minority government.

Lester Pearson

The Pearson government sought to be innovative, and in many ways it was — the armed forces were unified, social welfare was extended, and a distinctive new national flag was unveiled in 1964. The party also became ever more identified with the "politics of national unity," dedicated to containing Québec's sovereigntist aspirations. In reality all parties shared the need to deal with Québec's demands for changes in Canada's federal system.

These years were marked by personality quarrels and numerous Cold War-related political scandals, especially the Munsinger Affair. They were also notable for the establishment of the Canada Pension Plan and the signing of the Canada-U.S. Automotive Products Agreement, a treaty intended to give Canada a larger share of the continental auto market. Desperate to escape from the minority straitjacket, Pearson called an election for 8 November 1965. He won only two more seats, remaining two short of a majority.

Centennial and Expo

In 1967, Canada marked its Centennial birthday, and the world came to celebrate in Montréal at Expo 67 — a world's fair notable for the striking architecture of many of its pavilions, including the U.S. contribution: a giant geodesic dome. Montréal, then Canada's largest city, had come into its own as a confident, stylish and multilingual metropolis.

That same year the Conservatives replaced Diefenbaker with Nova Scotia Premier Robert Stanfield. Pearson resigned at the end of 1967, to be succeeded by Pierre Trudeau, who largely restored party unity. The choice of Trudeau emphasized the Liberals' commitment to finding a solution to the "Québec problem." Trudeau's vigorous opposition to Québec nationalism (see French Canadian Nationalism) and "special status" won support in English Canada, while his promise to make the French fact important in Ottawa — through official bilingualism, for example — appealed to his fellow Francophones. Conservatives and the NDP found difficulty in developing a similarly appealing platform, not least because both lacked support in Québec. In 1968, Québec's place in Confederation and Trudeau's personality dominated federal political debate. This dominance endured almost uninterrupted into the 1980s.

Pierre Trudeau

In 1968 Trudeau took the country by storm — winning a majority by appealing across class lines and even across regional barriers with his personal charisma and his 60s-era insouciance. Canadians hadn't seen a politician like him. The Liberals won more seats west of Ontario than since 1953. Over the next few years, Trudeau's harsh response to terrorism in Québec during the 1970 October Crisis, the growth of leftist sentiment in the NDP, and Conservative leadership bickering strengthened Trudeau's position. However, when he called an election for 30 Oct 1972, the Liberals' position was considerably weaker. Their emphasis on biculturalism angered many English Canadians who feared fundamental changes in their lives and their nation; many were also unhappy with the cuts in defence and particularly in the forces dedicated to NATO. The Liberals were returned to power but with only a minority government, supported by the NDP under leader David Lewis.

(1972-1980) The Inflation Curse and Regional Divides

A month before the 1972 election, Canadians were glued to their television sets, watching an unfolding international drama that was a mixture of politics and hockey. Amid Cold War tensions, the best hockey players from Canada and the Soviet Union squared off in the 1972 Summit Series. Paul Henderson scored the most famous goal in hockey history, winning the series for Canada on September 28 in Moscow. But it was a narrow victory, and the Soviets had shaken Canadians' confidence in themselves as the finest hockey players on the planet.

Parti Québecois

Two years later, Canadians were back at the voting booth in the 1974 federal election. Trudeau's reformist legislation and his opposition to the Conservative policy of anti-inflation wage and price controls brought many working-class voters to his side, especially in BC and Ontario. The Liberals won another majority, dependent for their support upon Québec and urban Ontario. After 1974 Trudeau gave indecisive leadership. Personal problems, weakness in his cabinet and intractable economic difficulties — including oil-price shocks and other inflationary pressures — plagued his government between 1974 and 1979. He surged in popularity in 1976-77 when René Lévesque's Parti Québécois gained power in Québec, prompting fears in English-speaking Canada about national unity, which many considered Trudeau well-equipped to handle.

In 1976, Montréal once again became the focus of world attention as host of the 21st Summer Olympic games. Innovative, though ultimately costly, new facilities were built including a distinctive concrete stadium (nicknamed "the Big O). For the first time in Olympic history, the host nation did not win a gold medal.

Joe Clark

Three years later, in May 1979 Opposition leader Joe Clark defeated Trudeau — losing Quebec but sweeping English Canada — for a minority Conservative government. In December the Clark government presented a tough budget and lost a subsequent non-confidence motion, and an election was called for February 1980. Cleverly manipulating the Conservatives' internal differences, the Liberals under Trudeau (who had resigned and then returned) regained their majority in an election in which Ontario swung strongly behind the Liberals, whose policies on energy resource pricing they favoured and the West abhorred. The Liberals won no seat west of Manitoba and only two there. Deep regional divisions in Canadian politics resulted from economic strategies marking a fragmented party system, which mirrored a fragmented nation.

Terry Fox

In the summer of 1980 a young man with only one leg ignited the interest of Canadians the way no politician could. Terry Fox's cross-country Marathon of Hope began in Newfoundland and ended on the Trans-Canada Highway at Thunder Bay, Ont.—only halfway to Fox's Pacific goal. Fox died the following summer, but by then he was a national icon, and the annual Terry Fox Runs he inspired would go on to raise hundreds of millions of dollars for cancer research, in countries around the world.

(1981-1992) The Constitution Decade

After 1980, Trudeau's government followed a nationalist course for a time. The National Energy Program offered great incentives to encourage domestic ownership in the petroleum industry, but it was seen in the West, especially Alberta, as meddling with provincial resource rights. Trudeau was also instrumental in keeping the country unified, by campaigning along with other "No" forces in the 1980 Québec referendum on sovereignty association.

Trudeau then set out to "patriate" the Canadian Constitution from Britain, and to create the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and entrench it in the new Constitution. After a long series of negotiations with provincial leaders, the patriated Constitution was signed in Ottawa in 1982 by Queen Elizabeth — but it left a festering political problem because Québec's René Lévesque, alone among the premiers, had refused to endorse the document.

Brian Mulroney

Trudeau became ever more unpopular as inflation, interest rates and unemployment rose, and in 1984 the Liberals paid the price. The Conservatives had replaced Clark with a bilingual Quebec business executive, Brian Mulroney, in 1983. The Liberals chose John Turner as Trudeau's successor a year later. Turner quickly called an election. The result was an overwhelming Conservative victory.

In Ottawa meanwhile, Mulroney had tried and failed to win the Quebec government's endorsement of the Constitution via the Meech Lake constitutional accord, which became the central political drama of his first term in office. His government also negotiated a contentious free trade agreement with the U.S., which became a major election issue in 1988. Mulroney won another, though smaller, majority government and in 1989 Canada and the U.S. began a new trading regime that was later expanded to include Mexico. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) contributed to a greater integration of the North American economy and, its critics would argue, a harmonization a weakening of Canadian cultural protections.

Outside the political arena, two very different dramas captured Canadians' attention during this time. On 23 June 1985, an Air India Boeing 747 flying from Toronto and Montreal to London, was blown up over the Atlantic, killing all 331 people on board, including 268 Canadians, mostly of Indian ancestry. The worst terrorist attack in Canadian history revealed deep flaws in Canada's domestic police and security services. It also led to a 20-year investigation and prosecution that yielded the conviction of only one conspirator, Sikh-Canadian Inderjit Singh Reyat.

In 1988 Calgary welcomed the world to the Winter Olympics. The city put on a party the likes of which the winter games had never seen. But once again, as in Montreal, the host nation failed to win a gold medal.

Two Failed Accords

In 1990, the Meech Lake Accord officially died, after several years of failed efforts to win approval among all the provincial governments. Québec reacted angrily, as did a handful of Mulroney's Quebec MPs, who quit the Conservative caucus to form the separatist Bloc Quebecois in Parliament, under the leadership of former cabinet minister Lucien Bouchard. Wounded, but still pressing for a constitutional solution, the Mulroney government and the provinces worked out a new deal called the Charlottetown Accord (see Charlottetown Accord: Document). Despite support from all of the major parties and provincial governments, the Accord was also rejected — this time in a national referendum in October 1992. The rejection was probably as much the result of the angry public mood created by the worst postwar recession as the contents of the Accord itself. Canadians were also weary after more than a decade of constitutional wrangling, which had dominated the national agenda.

(1993-2005) Liberal Hegemony — and Collapse

In October 1993, the Liberals under Jean Chrétien were elected with a majority government. The Conservatives were reduced to only two seats, and the Official Opposition became the Bloc Québécois. Another Québec Referendum, in 1995, resulted in an exceedingly narrow victory for the "no" side.

Despite these national unity troubles, a buoyant economy and a fragmented opposition led to the re-election of the Liberals with a second majority in 1997. The Progressive Conservatives remained in the doldrums. However, the Reform Party — a western-based, right-wing, populist movement led by its founder Preston Manning — had its big breakthrough in 1997, becoming the Official Opposition. Yet in spite of its success, Reform had divided the conservative vote across Canada. Dislodging the Liberal hold on power appeared unlikely without some entente with the PCs. As Chretien governed, his opponents squabbled among themselves, with conservative voices increasingly calling for a serious effort to "unite-the-right."

Balancing the Budget

The federal government's budget deficits had reached alarming levels by the 1990s, and Chrétien and his finance minister Paul Martin embarked on an aggressive program to cut spending and balance the budget, which they did in 1998. The Liberals were aided in this effort by revenues from the Goods and Services Tax (GST), introduced by Mulroney, and by downloading some federal costs to provincial governments. Nevertheless, they produced Canada's first balanced budget in 30 years.

The following year the largely self-governing Inuit homeland of Nunavut was officially created across two million square kilometres of the eastern Arctic, becoming Canada's third territory.

War in Afghanistan

Canadians welcomed the new millennium in 2000, and re-elected the Chrétien Liberals with a third majority government. The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, soon transformed government agendas across the western world, especially Canada, which now faced rampant American security concerns over their long, undefended northern border. Canadians played a unique role on "9/11," particularly on the East Coast, offering refuge and hospitality to airline passengers from the hundreds of trans-Atlantic aircraft diverted to Canadian airports.

In 2002, Chrétien dispatched a small number of troops to join the U.S. counter-terrorism effort in Afghanistan — a military commitment that ramped up considerably in 2006, when Canada sent a battle group to fight Taliban insurgents around the southern Afghan city of Kandahar. Over the next eight years, 158 Canadian soldiers would die in Afghanistan, and hundreds more would be wounded.

Paul Martin Takes Helm

In 2003, after a period of Liberal infighting, Chrétien was replaced as party leader and prime minister by Paul Martin. Martin took over a party that had grown complacent in power, and was beset by a growing scandal over the abuse of government funds, by Liberal-friendly firms in Quebec. Martin tried to deal with the "Sponsorship Scandal," as it was called, by appointing a public inquiry, which found evidence of illegal kickbacks of cash to the Liberals by Quebec businessmen who had received government contracts.

Although Martin was personally exonerated by the inquiry, the Liberal brand took a beating. Under Martin they were reduced to a minority government in the 2004 election, and two years later they were defeated by the newly-united political right, under a new Conservative banner.

(2006-2014) Rise of the West

Stephen Harper ended 13 years of Liberal rule, winning a minority government in 2006. His Conservatives were handed a second minority in 2008, but captured their long-sought majority in Parliament in 2011 — an election that saw the NDP elevated to Official Opposition status for the first time in the party's history.

The Commodity Juggernaut

An Albertan, Harper's political rise coincided with an economic power-shift under way in Canada. Since Confederation the country's manufacturing heartland of southern Ontario and Quebec had provided the bulk of the country's wealth, and determined much of its politics. But in the 21st Century, the growing importance of Pacific Coast trade with Asia, and the vast oil (see Oil Sands) and mineral resources of B.C., Alberta and Saskatchewan made the West the economic engine of the country. On the East Coast, a smaller renaissance was taking place in Newfoundland and Labrador, where oil and other natural resources were turning once-poor provinces such as it (and Saskatchewan) into providers of jobs and exporters of wealth.

As if to reinforce Canada's new westward orientation, Vancouver hosted the Winter Olympics in 2010, and Canadian athletes captured the largest number of medals, to that date, in the country's Olympic history.

Economic Uncertainty

Despite its booming resource sector, Canada's economy was hit by the 2008 global financial credit crisis and subsequent recession, although the country's banks weathered the storm better than many other western nations. But the job losses, and the further erosion of the manufacturing base, took their toll on government finances, and Canada was once again running budget deficits. Even so, Harper was judged by many Canadians the leader best able to manage the economy.

One of Harper's main political goals since coming to office was to re-make the country along social and economic conservative lines, and to strike a blow against the Liberal Party, which had governed Canada for most of its history. In 2011 he'd succeeded in putting the Liberals into third place in Parliament. But the Conservatives had failed to make lasting inroads in the important political battleground of Quebec. And by 2013, the Liberals had a young, new leader from that province — Justin Trudeau, son of the former prime minister — threatening Harper's vision and the Conservative hold on power.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom