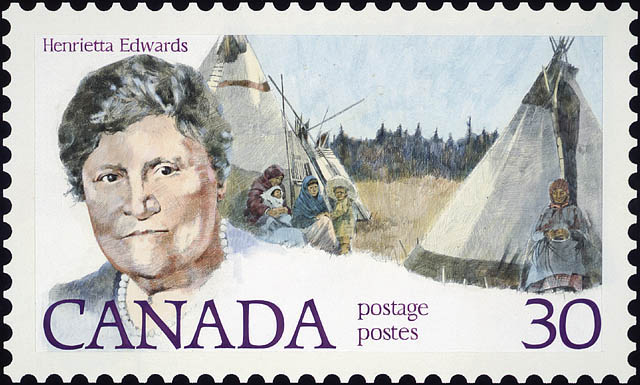

Henrietta Louise Edwards (née Muir), women’s rights activist, reformer, artist (born 18 December 1849 in Montreal, Canada East; died 9 November 1931 in Fort Macleod, AB). Henrietta Edwards fought from a young age for women’s rights and education, as well as women’s work and health. She helped establish many movements, societies and organizations aimed at improving the lives of women, and was instrumental in passing Alberta’s Dower Act in 1917. She was also one of the Famous Five behind the Persons Case, the successful campaign to have women declared persons in the eyes of British law. However, her views on immigration and eugenics have been criticized as racist and elitist. She was named a Person of National Historic Significance in 1962 and an honorary senator in 2009.

Early Life and Education

Henrietta Muir was one of seven children born to Jane and William Muir. The Muirs were a prosperous merchant-tailor family in Montreal. Strongly guided by their evangelical faith, the Muir family had built St. Helen’s Chapel — the first Baptist chapel in Montreal — as well as Montreal Baptist College.

According to historian Patricia Roome, Henrietta learned a great deal about women’s legal rights from her parents’ “democratic religious faith.” For example, her parents’ marriage contract was progressive for the time. It “guaranteed Jane [Muir] would have her own property and protected her from legal responsibility for William’s business obligations and personal debts.” Henrietta made a copy of her parents’ marriage contract before her own marriage in 1876. What’s more, her grandfather’s estate was divided equally among his children, regardless of gender — a stipulation of his will.

Henrietta was both home-schooled and sent to private schools in Montreal. There she encountered strong female role models — school principals and other organizers who advocated for women’s inclusion in academia. (See Women and Education.)

Philanthropy

In 1874, Henrietta Edwards asked that her father and other investors rent a house in Montreal. She and her sister Amelia used it as the Young Women’s Reading Room, a library and gathering place for religious meetings and social events.

The sisters also worked with the Working Girls Association (later, the Working Women’s Association; WWA). It was a philanthropic project to help young women get a good start towards independence. The WWA helped provide young women with affordable housing, training and support. It was backed by the Baptist Church, Edwards’s father and his colleagues. Henrietta, who was later made sole director, helped fund the association by selling her artwork.

Artwork

Henrietta Edwards was not able to enroll in art school in Montreal because she was a woman. She instead turned to private training. She went to New York City in 1876 to study under renowned portrait artist Wyatt Eaton. Edwards became an accomplished artist herself. She painted portrait miniatures of such prominent figures as Wilfrid Laurier (a personal friend) and Lord Strathcona. Her paintings were exhibited at the Art Association of Montreal, Ontario Society of Artists and the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts. In 1893, the federal government commissioned Edwards to paint a set of china for the Canadian pavilion at the Chicago World’s Fair.

Marriage and Family

In 1876, Henrietta married Dr. Oliver C. Edwards. (One of the guests at their small ceremony was Dr. William Osler, who was best man.) The newlyweds moved into the Muir home as Dr. Edwards established his medical practice. Between 1878 and 1885, the pair became parents to three children: Alice, William and Margaret.

Woman’s Work in Canada

In 1878, Henrietta Edwards and her sister Amelia launched Woman’s Work in Canada. The monthly publication is considered the first Canadian magazine for working women. The publication was unique in that it employed only women and trained them to print the publication themselves. Henrietta and Amelia also established the Montreal Women’s Printing Office in 1878. Meanwhile, Edwards continued to paint and exhibit her work from her studio. Proceeds from her artwork were funnelled into her philanthropic endeavours, including Woman’s Work.

Legal Expertise

In 1883, the Edwards family moved west to Indian Head, North-West Territories (now Saskatchewan), for Dr. Edwards’s job as government physician on First Nations reserves. Henrietta Edwards made time to study Canadian law informally, especially those codes concerning women and children. (See also Criminal Code of Canada.)

When her husband became ill in 1890, Henrietta Edwards and her family moved to Ottawa. Edwards met and later joined forces with Lady Ishbel Aberdeen, the Governor General’s wife, and helped her found several organizations. Edwards’s skills in organization, creating cohesive bylaws, and her talent for communications were indispensable in establishing the Victorian Order of Nurses, the National Council of Women of Canada (NCWC) and the Ottawa Young Women’s Christian Association. Lady Aberdeen appointed Edwards the convenor of the NCWC’s Law Committee.

At first, Lady Aberdeen was unsure about Edwards, writing that she was “not so well-known, not so practical and is rather aggressively evangelical for a post which will bring her much in contact with [Roman Catholics].” However, during the 30 years in which Edwards was convenor, she wrote two legal handbooks for women: Legal Status of Canadian Women (1908) and Legal Status of Women of Alberta (1916). The second edition of the latter was “issued by and under authority of the Alberta Attorney General” in 1921.

When associations needed help writing resolutions, petitions and official documents, they called on Edwards for her legal knowledge. Conversant in laws regarding women and children, she did not go to lawyers or judges for help; it was said that they came to Edwards for advice. Edwards did not attend law school, pass the Bar or possess formal legal training.

Women’s Suffrage in Canada

Dr. Edwards returned to Alberta and was struggling to make a living until he was appointed doctor to the Kainai (Blood) and Piikani (Peigan) in 1901. Two years later, the Edwards family settled near Fort MacLeod. Henrietta Edwards joined the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and also became vice-president of the North-West Territories chapter of the NCWC. It was through the WCTU that Edwards engaged in campaigns for women’s suffrage and equal rights. At the time, both the NCWC and WCTU focused on prison reform, financial allowances for women and equal grounds for divorce. However, the NCWC had yet to officially support women’s suffrage.

Edwards wrote about women’s suffrage in a 1900 NCWC handbook: “The woman is queen in her home and reigns there, but unfortunately the laws she makes reach no further than her domain…. If her laws, written or unwritten, are to be enforced outside, she must come into the political world as well — and she has come.”

Edwards campaigned tirelessly for women’s right to vote. She organized campaigns, passed around petitions and attended meetings. Women won the right to vote and hold provincial office in Alberta on 19 April 1916.

Dower Act (1917)

Assisting her husband on his medical rounds, Henrietta Edwards observed that Prairie women and children often struggled after divorce; or after husbands died; or when husbands sold the family house out from under his wife, even if the home was bought with her money. Edwards worked with judge Emily Murphy and independent MLA Louise McKinney to push the Dower Act (1917) through the Alberta legislature. The act was a vital piece of legislation that protected a married woman’s property rights. (see Dower.)

Persons Case

In August 1927, Emily Murphy, Canada’s first woman judge, invited Henrietta Edwards, Irene Parlby, Louise McKinney and Nellie McClung to a meeting at her Edmonton home. Murphy had carefully drafted a petition to put before the Supreme Court of Canada regarding the interpretation of the word persons in the British North America Act (now called the Constitution Act, 1867). At the time, women were not included in the definition of persons under the Constitution.

Murphy and the others signed the petition. Edwards’s signature appeared first; thus, the case was titled Edwards v. Attorney General of Canada. The petition asked the Supreme Court whether the word persons in Section 24 of the British North America Act, 1867 included women. If it considered women to be persons, the Constitution would allow for a woman to be appointed to the Senate.

Handing down the judgment on 24 April 1928, the Supreme Court denied the petition. The women — first called the “Alberta Five” and later the “Famous Five” — took their request to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in England (Canada’s highest court of appeal until 1949).

On 18 October 1929, after much deliberation, the Privy Council reversed the decision of the Supreme Court. It concluded that “the word ‘persons’ in sec. 24 does include women, and that women are eligible to be summoned to and become members of the Senate of Canada.” Lord Sankey, who delivered the judgement on behalf of the Privy Council in what became known as the Persons Case, also remarked that the “exclusion of women from all public offices is a relic of days more barbarous than ours […] and to those who ask why the word [persons] should include females, the obvious answer is why should it not.”

Edwards wrote the following year: “The rejoicing all through Canada was not so much that it opened the door of the Canadian Senate to women, as it was that it recognized the personal entity of women, her separate individuality as a person.”

Eugenics

Like other members of the Famous Five, Henrietta Edwards has been criticized as being elitist and racist, and for supporting the eugenics movement. Eugenics was a pseudoscience that subscribed to the idea that the human population could be improved by controlling reproduction. Many influential Canadians, including J. S. Woodsworth, Dr. Clarence Hincks and Tommy Douglas, supported eugenic ideas in the early 1900s. (See Tommy Douglas and Eugenics.) They promoted both “positive” eugenics (promoting the breeding of “fit” members of society) and “negative” eugenics (discouraging procreation by those considered “unfit”). Eugenicists argued that “mental defectives” and the “feeble-minded” were prone to alcoholism, promiscuity, mental illness, delinquency and criminal behaviour, and therefore posed a threat to the moral fabric of the community. These concerns led to increasing support for eugenic legislation, including the sterilization of “defectives.”

Edwards also possessed nativist — or prejudiced — views of non-Anglo immigration. Her views on race were complex. As convenor of the NCWC Law Committee, she sought legal equality for Indigenous women, as she wrote, “such legislations as will raise the social status of our Indian women and afford her equal legal protection with our white women.” Edwards was appointed as an NCWC representative to the Social Service Council's Committee on Indian Affairs in 1921. But her ideas were not considered by the Department of Indian Affairs.

In 1928, Edwards was appointed to the Alberta government’s Advisory Committee on Health. During this time, the Sexual Sterilization Act (1928) was passed; it was in effect until 1972. Edwards believed that the law would help bring an end to “moral perversion.” A similar law was also passed in British Columbia (1933–73). During that time, thousands of people deemed “psychotic” or “mentally defective” underwent forced sterilization. A disproportionate number of them were Indigenous women. (See also Sexual Sterilization of Indigenous Women in Canada.)

Legacy

Henrietta Edwards died on 9 November 1931 in Fort Macleod, Alberta. She was 81 years old.

In 1962, she was named a Person of National Historic Significance by the Government of Canada. In October 2009, 80 years after the Persons Case, the Senate of Canada voted to recognize the Famous Five as honorary senators. It was the first time the Senate had bestowed such a distinction.

Comics artist Kate Beaton illustrated a Google Doodle published on 18 December 2014 to celebrate Edwards on what would have been her 165th birthday. Said Beaton: “Henrietta was a woman who made things happen and fought for it all with unflappable conviction. Canada is a richer country for having her as a citizen.”

See also Women’s Movements in Canada; Status of Women; Royal Commission on the Status of Women in Canada; Council on the Status of Women; Women and the Law; Women’s Organizations.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom