Coins are issued by governments for use as money. A quantity of coins issued at one time, or a series of coins issued under one authority, is called a coinage. Tokens are issued as a substitute for coinage, usually by private individuals or organizations such as merchants and banks. Canada’s complex political history has meant that Canadian numismatists have an astonishing variety of coins, coinages and tokens to collect and study.

First Coins in Canada

The earliest coins in use in what is now Canada were those carried by the first colonists and visitors to our shores. French coins predominated along the St. Lawrence and in other areas under French control (see New France). English coins were most common in their territories, and a mix of coins from Portugal and elsewhere dominated along the coast, particularly in Newfoundland, where various nationalities came to fish (see Fisheries History).

French Coins

The first coins struck for use anywhere in Canada were the famous “GLORIAM REGNI” silver coins of 1670, struck in Paris for use in all French colonies in the Americas. Few specimens have been found in Canada; the piece of 15 sols is especially rare. In 1672, the value of these coins was raised by one-third in a vain attempt to keep them in local circulation. None was in use after 1680.

In 1717, there was an attempt to produce a copper coinage for the French colonies, but few were struck because of the poor quality of the available copper. In 1721 and 1722, an issue of copper coins of 9 deniers was struck for all French colonies and a large shipment was sent to Canada. There was considerable resistance to their circulation and, in 1726, most of the coins, which had lain unissued in the treasury at Quebec City, were returned to France.

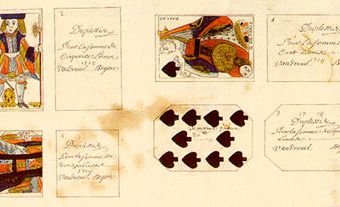

These coinages were inadequate for Canada’s needs and French coins were shipped out annually. The French ship Le Chameau carried treasure intended to supply the colonial governments in Quebec and Louisbourg, but it was lost in a hurricane off Cape Breton Island in 1725. The authorities at Quebec also issued various kinds of paper money (see Playing-Card Money), eventually far too much of it, and at times had to permit the use of large, silver Hispano-American 8 real pieces, called Spanish dollars, and their subdivisions.

British Coins

For the first 50 years after the Conquest (1760), the British did almost nothing to provide coin, other than sending an occasional shipment of badly worn copper withdrawn from circulation in Britain. Gold coins consisted of British guineas and, later, sovereigns, some American eagles, French louis d’or, Spanish doubloons (and fractions thereof), and small quantities of Portuguese gold.

Silver coins comprised mostly Spanish coins struck in Mexico and South America, some old French silver circulating in Lower Canada, and a sprinkling of English silver elsewhere. American silver appeared after 1815. Copper coins consisted of an insufficient and dwindling supply of battered, worn-out English and Irish halfpennies dating from the reign of George III, supplemented by locally issued and imported tokens and by small numbers of American cents and various foreign coins. Anything the size of a halfpenny would pass for one in Montreal between 1820 and 1837.

Prince Edward Island

During this period in PEI, various tokens were also in use. Large numbers of lightweight halfpenny tokens circulated from about 1830 till well after 1860. The most numerous were the SHIPS COLONIES & COMMERCE halfpennies and tokens inscribed “SUCCESS TO THE FISHERIES” or “SELF GOVERNMENT AND FREE TRADE.”

Newfoundland and Labrador

The earliest private tokens in Newfoundland and Labrador date from the 1840s and include the issues of Peter McAusland and the Rutherford Brothers, who operated stores in St. John’s and Harbour Grace. In later years, large numbers of SHIPS COLONIES & COMMERCE tokens were imported from Prince Edward Island. Following several attempts by the local government to ban the importation of tokens in the 1850s, additional local issues were circulated. These issues were anonymous and included a piece dated 1858 picturing a ship, and another dated 1860 that reads “SUCCESS TO THE FISHERIES.”

With the adoption of the decimal system in 1863, the value of private tokens was reduced and a decimal coinage was instituted. The coinage consisted of bronze cents, silver 5-, 10-, 20- and 50-cent pieces and gold $2 coins. The lowest denominations were issued variously between 1865 and 1947. The 20-cent pieces were issued from 1865 to 1912. In 1917, and again in 1919, a 25-cent piece was issued. The 50 cent coins were issued variously between 1865 and 1919. The $2 pieces were issued from 1865 to 1888. Coins were struck at the Royal Mint in London, and on occasion at the Heaton Mint. The Mint in Ottawa struck coinage for Newfoundland and Labrador during the First World War and Second World War and again in those years immediately preceding Newfoundland and Labrador’s entry into Confederation in 1949.

Nova Scotia

In 1813, certain Halifax businessmen began importing halfpennies into Nova Scotia and, by 1816, a great variety was in circulation. The government ordered their withdrawal in 1817. Beginning in 1823, and again in 1824, 1832, 1840 and 1843, the government issued a copper coinage, without authority from England. In 1856, Nova Scotia issued one of the most beautiful of the Canadian colonial coinages, bearing an image of a mayflower, with the permission of the British government.

New Brunswick

An anonymous halfpenny appeared in Saint John about 1830. In 1843, the government issued copper pennies and halfpennies without authority from England. These were followed in 1854 with another issue, this time with the permission of the British authorities.

Lower Canada

Lower Canada (what is now Quebec) had the greatest number and variety of tokens in circulation. The Wellington tokens, a series of halfpenny and penny tokens with a bust of the duke of Wellington, appeared in about 1814. They were popular, and many varieties were issued locally after 1825. In 1825, a halfpenny of Irish design was imported; its popularity resulted in its being imitated in brass, copies of which are very plentiful. In 1832, an anonymous halfpenny of English design appeared and was extensively imitated in brass. Counterfeits of worn-out English and Irish George III coppers also circulated in large numbers. These counterfeits were called “blacksmith tokens” as they were popularly believed to have been struck by a Montreal blacksmith to pay for his drink. This period ended in 1835, when the banks refused to accept such nondescript copper, except by weight.

The Bank of Montreal circulated sous or halfpennies with a bouquet of heraldic flowers on one side and the value in French on the other. These sous were immediately popular, and the government allowed the bank to supply Lower Canada with copper; however, the sous were very soon imitated anonymously. The imitations were accepted because there was a dearth of small change with which to conduct business; but they became too numerous and, once again, the banks had to refuse them, except by weight.

To replace them, the government authorized four banks — the Bank of Montreal, the Quebec Bank, the City Bank and La Banque du Peuple — to issue copper pennies and halfpennies with the arms of Montreal on one side and a standing habitant on the other. These coins arrived in Canada just as the rebellion of 1837 began and were issued in 1838.

Upper Canada

Upper Canada (what is now Ontario) first used local tokens after 1812, when a series of lightweight halfpennies was issued in memory of Sir Isaac Brock. These were superseded after 1825 by a series of tokens with a sloop on one side and various designs (e.g., plow, keg, crossed shovels over an anvil) on the other. In 1822, a copper twopenny token was issued by Lesslie & Sons. The firm also issued halfpennies from 1824 to 1830. There were no government issues in Upper Canada.

When the two Canadas were united in 1841, the Bank of Montreal was allowed to coin copper; pennies and halfpennies appeared in 1842. Halfpennies were issued again in 1844. After 1849, the Bank of Upper Canada received the right to coin copper, and large issues of pennies and halfpennies appeared in 1850, 1852, 1854 and 1857. The Quebec Bank was allowed to issue pennies and halfpennies in 1852.

Vancouver Island, British Columbia and the Hudson’s Bay Company Territory

There was little need for coinage in the territories controlled by the Hudson’s Bay Company; the fur trade depended primarily on barter, although brass tokens (see Made Beaver) served the purpose of coinage. In colonial British Columbia, very few coins were in circulation. Small shipments of English silver and gold were sent to BC in 1861 and these coins, with American coins, were used until after Confederation.

The Decimal System

The decimal system was first adopted by the Province of Canada (the united colonies of Lower and Upper Canada) in 1858, based on a dollar equal in value to the American dollar. American silver had become very plentiful and trade with the US made it necessary to adopt a decimal system. New Brunswick and Nova Scotia followed in 1860; Newfoundland, in 1863; PEI, in 1870.

The coinage of the Province of Canada consisted of silver 5-, 10- and 20-cent pieces dated 1858 and bronze cents dated 1858 or 1859. Nova Scotia issued bronze cents and half cents in 1861 and 1864, cents alone in 1862; New Brunswick, cents in 1861 and 1864, and silver coins like the Canadian ones in 1862 and 1864; PEI issued a cent in 1871. Newfoundland’s coinage began in 1865. All of these coins became legal tender in the Dominion of Canada after the various provinces entered Confederation.

1870 to the Present: Coins

The first coins of the Dominion of Canada, issued in 1870, were silver 5-, 10-, 25- and 50-cent pieces. Bronze cents were added in 1876. All coins bore on the obverse the head of Queen Victoria. Silver coins bore the value and date in a crowned maple wreath on the reverse; the cent bore the value and date in a circle enclosed by a continuous maple vine. These coins were variously issued until 1901. In 1902, the crowned bust of Edward VII replaced the head of Queen Victoria. In 1911, the crowned bust of George V replaced that of Edward VII.

In 1937, a completely new coinage was introduced after George VI ascended the throne. For the first time, each denomination had its own pictorial reverse design. With some modifications, the same designs are on today’s coinage. All denominations bore a splendid bare head of George VI. The reverse of the cent shows two maple leaves on a common twig; the nickel, a beaver chewing a log on a rock; the dime, a schooner closely resembling the famous Bluenose; the quarter, the head of a caribou; the 50-cent piece, the Canadian coat of arms; the dollar, a voyageur and Indigenous person in a canoe, with a wooded islet in the background.

In 1953, a bust of a young Elizabeth II wearing a laurel wreath replaced the head of George VI. This was the first of four portraits of the Queen to be used to date. In 1965, a draped, mature bust of the queen wearing a tiara was introduced, and in 1990 this was replaced by the crowned effigy, designed by Dora de Pédery-Hunt. In 2003, the Royal Canadian Mint introduced a fourth effigy, by artist Susanna Blunt, depicting the Queen with a bare head.

In the summer of 1967, the silver content of the dime and quarter were reduced from 80 per cent to 50 per cent and production of 50-cent pieces and dollars for general circulation was stopped. In 1968, the regular designs were resumed, the dime and quarter being in 50 per cent silver. In August 1968, nickel replaced silver entirely for general circulation and a reduced 50-cent piece and dollar were coined in nickel.

In 1987, a dollar coin was introduced to replace the dollar bill, which was discontinued in 1989. The new coin was 11-sided and struck in aureate bronze-plated nickel. It was nicknamed the loonie because of the loon illustrated on the reverse (see Canadian Dollar). On 19 February 1996, the $2 coin was introduced into circulation. Called a “toonie,” it is a bi-metallic coin in nickel and aluminum bronze featuring a polar bear designed by Brent Townsend. At the same time, the Bank of Canada stopped issuing the $2 bill.

In 2000, the Bank of Canada stopped issuing the $1,000 note and the Mint began circulating nickel-plated 5-cent pieces in an effort to curtail minting costs. It was determined that dropping the penny would save the country $11 million a year, and on 4 February 2013, the Royal Canadian Mint ceased distribution of the coin to banks and other financial institution (see also A Penny Dropped: Abolishing the Cent?).

1870 to the Present: Tokens

The colonial tokens of the pre-Confederation period quickly disappeared from circulation after 1870 as their use was curtailed by legislation and their place was taken by ever-increasing quantities of the new Canadian coinage. From about 1890 to the period between the First and Second World Wars, local merchants across Canada issued large quantities of variously shaped trade tokens that were exchangeable for a variety of goods and services, such as a loaf of bread, a pint of milk, a shave or a ride on the electric railway. Their use declined with postwar improvements in transportation and technology.

Commemorative Coins

In 1935, the silver dollar was first coined to commemorate the silver jubilee of the reign of George V. This dollar inaugurated a very popular series of Canadian coins. Except for the war years 1939 to 1944, silver dollars were coined every year until 1967.

Special commemorative dollars were struck in 1939 for the royal visit to Canada; in 1949, for the entry of Newfoundland into Confederation; in 1958, for the centenary of the creation of the Crown Colony of British Columbia; in 1964, for the centenary of the Charlottetown Conference and the Quebec Conference; and, in 1967, for the centenary of Confederation.

In 1967, a special coinage, commemorating the centenary of Confederation, was issued. Each coin bore the bust of the Queen on the obverse. The cent featured a dove in flight; the 5-cent piece, a hare; the 10-cent piece, a mackerel; the 25-cent piece, a bobcat; the 50-cent piece, a howling wolf; and the dollar, a Canada goose in flight. The motifs were created by artist Alexander Colville.

In 1971, commemorative dollars were struck in 50 per cent silver and sold in individual cases. Issued each year since, they commemorate special events. Special sets of sterling silver $5 and $10 pieces were struck from 1973 to 1976 to commemorate the 1976 Olympic Games, held in Montreal. The gold $100 piece, struck in 1976 for the same event, is the first of a beautiful series of gold coins struck annually for sale to collectors. From 1985 to 1987, a series of 10 sterling silver $20 pieces was struck to commemorate the 1988 Winter Olympic Games held in Calgary.

Through the 1990s and into the 21st century, the Mint has continued to strike a variety of non-circulating commemorative coins. Their products have included a silver 3-cent piece to commemorate Canada’s first postage stamp; silver 10-cent pieces commemorating the 500th anniversary of John Cabot’s voyage and Alphonse Desjardins, the founder of the caisse populaire; silver 50-cent pieces highlighting Canada’s flora, fauna and Canadian sport; $15 coins featuring the 12 signs of the Chinese lunar calendar and $20 coins honouring pioneers of aviation. Special sets have also been issued to commemorate the 90th anniversary of the opening of the Mint in 1908, the striking of Canada’s first silver dollar in 1911 and the issue of Canada’s gold $5 and $10 coins in 1912.

Many of these coins have served as proving grounds for innovations in minting technology. New features on coins have included gold cameos, colourized parts of the design and holograms.

Canadian Rarities

The rarest Canadian decimal coins are the 50-cent piece of 1921, the 5-cent piece of 1921, the dotted 1936 cent and 10-cent pieces, the 10-cent piece of 1889, the 50-cent piece of 1890 and the 10-cent piece of 1893, with a round-topped numeral 3. Most of the strikings of 1921 were never issued. After remaining in the vaults of the Mint for some time, they were melted down.

The dotted 1936 coinage was intended to be an extra issued from the 1936 dies to supply Canada’s needs, pending the arrival of the 1937 dies. A hole punched into the bottom of the reverse dies produced the dot. Very few specimens are known. The other coins mentioned are rare because the coinages of those years were very small.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom