Canadian Architecture: 1867-1914

Between Confederation (1867) and the outbreak of the First World War (1914), Canada's development from British colony to modern, largely urban, industrial and effectively self-governing nation was reflected in its architecture. By 1914 western Canada had been annexed and settled; the country had expanded from a cluster of provinces hemmed in by the Atlantic seaboard and the Great Lakes to a country claiming sovereignty over the whole northern half of the continent. Under capitalism and liberalism, finance and industry assumed new importance, creating two substantial metropolises, Montréal and Toronto; by 1911 Montréal had almost 500,000 residents, Toronto well over 300,000. Several regional centres were also flourishing, with Winnipeg and Vancouver in the lead. The federal government's nationalistic mercantile policies gave it an expanded presence in Canadian society, one reflected in government building of the period. Foreign influence in architecture swung mainly from British to American; but, in architecture as in culture generally, Canadians sought unique forms to express the character of their youthful country. Less than half a century of rapid change had resulted in something approximating an architectural revolution.

Status of the Profession

In 1867 architecture was a marginal pursuit and, where practised, was dominated by Victorian stylistic revivals. Most building was vernacular (copied from known and traditional models) and anyone could call himself an architect. Professionally trained designers were few although a small number of British trained architects had established themselves in major Canadian towns in the two decades before Confederation. One of these, Thomas FULLER, had just completed the Canadian PARLIAMENT BUILDINGS in Ottawa (Fuller & Jones, 1859–66), a forceful version of High Victorian Gothic that was destined to exercise long-term influence on Canadian public design. A holdover from the Renaissance Revival of the 1830s–50s, the Italianate style, usually rendered in brick, with bracketed cornices (often wooden) and rows of round or flat-arched windows, dominated commercial streets. Houses, except large and expensive ones built according to fashionable styles, were usually plain and wooden, with their side or gable ends turned to the street. More public, self-conscious design was under the sway of what is termed "Picturesque Eclecticism."

Late Nineteenth 19th-Century Styles

In the 1870s, the Second Empire style, French in origin, American by adoption and marked by rich classical sculptural effects and high mansard roofs (sometimes slate), was the dominant mode for public buildings. The style was applied to hotels, railway stations, city halls — especially Montréal's Hôtel de Ville (H.M. Perrault, 1872–78) — and provincial legislatures, including those of Québec (E.E. Taché, 1877–87) and New Brunswick (Charles Dumaresq, 1880–82).

The federal government also employed Second Empire in most of its buildings of the 1870s, notably the large, lavish custom house at the port of Saint John, New Brunswick (McKean and Fairweather, 1877–81).

Second Empire styles were even applied to domestic design, especially when the designer and owner wanted to make a grand statement. William Tutin THOMAS's design for Shaughnessy House, built 1874–75, shows the typical mansard roof with delicate cast-iron work at the top.

Churches and other prominent semi-public building types of the period still tended to rely on Victorian Gothic and would do so for several decades yet, as Joseph Connolly's (RC) Church of Our Lady in Guelph, Ontario (1876–1926), suggests. Some Catholic churches, however, most prominently Montréal's Cathedral of Mary Queen of the World (Joseph Michaud, Victor Bourgeau and Étienne-Alcibiade Leprohon, 1870–94), favoured a revived version of Roman Baroque, with a Counter-Reformation flavour.

Despite the precedent of the federal Parliament, Victorian Gothic was less adaptable to large public buildings, though examples can be cited from as late as the mid-1880s. BARBER & BARBER's Winnipeg City Hall (built 1884–86), and often referred to as the "gingerbread" city hall, is a notable, if eccentric, example.

Economic Expansion and New Styles

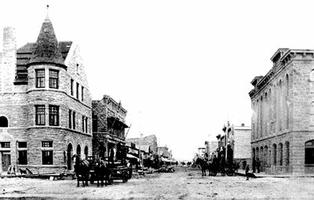

The decade 1885–95 was an architectural watershed in Canada. In a time of cyclical economic booms and busts it was a period of relative prosperity marked by rapid large-scale building. The transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) was completed in 1886, opening the western prairies to settlement and cementing Montréal's dominance of Canadian finance and transportation.

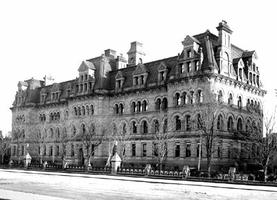

The federal government, under the leadership of John A. MACDONALD and the Conservatives, built for itself aggressively and, with Fuller serving as chief architect for the Department of Public Works from 1881 to 1896, built a fleet of federal buildings across the country. The largest was the Langevin Block in Ottawa (1883–88), but local buildings accommodating federal government functions were also built, including postal and customs facilities, prisons and courthouses.

It was during this decade that new building types appeared in Canada, many influenced by building forms developed in the United States in the period of growth which followed the Civil War there. The tall office building, the comprehensive department store, the domed legislature, the apartment house, and the Protestant church designed as an amphitheatre all entered Canada in the 1880s or 1890s.

Professionalization of Architecture

The decade between 1885 and 1895 witnessed the organizing and professionalizing of architecture, its conversion to a recognizable modern form. Architects in several provinces federated into professional institutes with codes of ethics and powers over training and legislation. The Ontario Association of Architects formed in 1889; similar bodies began in Québec and British Columbia in 1890–92. A professional journal, Canadian Architect & Builder, began in 1888, and the first architectural school in a Canadian university opened at McGill in 1896.

Changes within the practice of architecture were accompanied by the appearance of a new style — imported from the United States — which dominated public design, and some private as well, until almost 1900. This was the neo-Romanesque manner pioneered by American architect Henry Hobson Richardson. Its hallmarks are large, rhythmically spaced, round-arched openings and strongly coloured and textured masonry. Richardson deployed it as an all-purpose mode, picturesque enough to appeal to late Victorian eyes yet susceptible to the discipline he had acquired in a Beaux-Arts training in Paris. In North America in the 1880s the style swept all before it.

Richardsonian Romanesque

The Richardsonian Romanesque style, a type of Romanesque Revival architecture named after American architect Henry Hobson Richardson, made its first prominent Canadian appearance in Richard Waite's design for the Ontario Legislature (1886–92) and in churches and commercial buildings in Toronto designed about 1886 by Edmund Burke and E.J. LENNOX. Soon Richardsonian Romanesque was everywhere. The largest Canadian building in the style was Toronto's City Hall, by Lennox, of 1889–99. The style was especially useful for commercial purposes in stores and warehouses thanks to the precedent of Richardson's Marshall Field warehouse-store in Chicago (1885–87) and to the rugged masculinity of the mode, a quality Victorians associated with commerce. Winnipeg's J.H. Ashdown warehouse (first portion by S. Frank Peters, additions by J.H.G. Russell, 1895–1911) is a fine example.

Besides appearing in its pure form, the Beaux-Arts style could also be modified to suit Canada's diversity. Many stations and hotels built by the CPR showed a French late-medieval, early Renaissance character that has been labelled "Château Style." An example of this style is Montréal's Windsor Station (original portions by Bruce Price, 1888–89, with later additions).

The Château Frontenac in Québec City (original portions by Bruce Price, begun 1892) and the Banff Springs Hotel, in both its early (Bruce Price, 1886–88) and present (W.S. Painter, 1911–14, and J.W. Orrock, 1925–28) versions, are examples. Despite stylistic differences between them, all manifest the pleasure the period took in vigorous yet learned neo-medieval design.

The Richardsonian style could also be varied to give it a more British character; this appealed greatly to coastal British Columbia. F.M. RATTENBURY's Parliament Buildings in Victoria, of 1893–97, besides recalling Richardson's work, evoke English and Anglo-Indian Imperial precedents and the dome of R.M. Hunt's Administration Building at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. Craigdarroch Castle (W.H. Williams, 1887–90), also in Victoria, has a Franco-Scots feeling.

Queen Anne Revival

As Richardsonian Romanesque dominated public, commercial and religious architecture, so the Queen Anne Revival held sway in house design from the mid-1880s to almost 1910. A hybrid mode rooted in early 18th-century design in England which became the speciality of such English architects as R.N. Shaw and J.J. Stevenson, Queen Anne Revival was marked by the pervasive use of red brick, often trimmed with light, pretty ornament, such as fans and sunflowers, of wood, moulded brick or terracotta. Rarely is the style found in its pure form in Canada, though examples, such as the massive house of lumber baron J.R. Booth in Ottawa (J.W.H. Watts, 1909) can be cited. The style's real importance lay in the variety, intimacy and picturesqueness it gave to countless small detached and row houses and small to mid-sized apartment houses in a period when mass housing close to downtown was in demand in Canada. The endless rows of red-brick houses lining the gridded streets east and west of downtown Toronto are an example. So are apartment houses such as the Roslyn Court and DeBary Apartments in Winnipeg (W.W. Blair, 1909, and C.S. Bridgeman, 1912, respectively).

As the Richardsonian fashion suggests, a key theme in Canadian architecture by the 1880s was cultural pressure from the United States. Prestigious design commissions often went to American architects, such as Price and Waite. It was partly to exclude American architects that the professional licensing bodies were formed, but also to lift standards of Canadian education and practice so Canadians could compete with them on an equal footing. Besides direct involvement, American influence entered Canada in two crucial ways. One was the emergence of a so-called commercial style in department stores and tall office buildings, and the other was the neoclassical Beaux-Arts style.

Commercial Style

Office buildings, as a type, developed mainly in the United States and first appeared in Canada in the 1880s. Early ones, however novel their height and structure, were rendered in historic styles. The New York Life Insurance building of 1888 (Babb, Cook & Willard, of New York), at eight storeys plus a tower, was Canada's first skyscraper; round-arched Richardsonian in facade treatment, it makes allusions to late-medieval Italian house towers. The Confederation Life building in Toronto (Knox, Elliot & Jarvis, of Chicago, 1890–91) is, in Harold Kalman's words, "a romantic Romanesque-Gothic castellated fantasy." These early tall buildings had load-bearing masonry walls but made limited use behind them of structural metal. A fireproofed all-steel skeleton, made possible only as structural steel dropped in price, was introduced in 1895 in the rebuilding of the Robert Simpson department store in Toronto (BURKE & HORWOOD). For it Edmund Burke devised a frank, boxy, virtually non-historicist external treatment, expressive of the steel cage within.

Treatments equally rational but coloured by Beaux-Arts influence became the norm after 1900, and by the First World War even mid-sized Canadian cities had 8- to 10-storey office buildings. Vancouver's Henry Birks building (1912–13, Somervell & Putnam, of Seattle), of 10 storeys plus a mezzanine, was built over a frame of reinforced concrete and elegantly clad in white terracotta. Department stores, requiring large open areas uncluttered by posts, were a related phenomenon. Hudson's Bay Company stores appeared across the West in suave versions of Edwardian Baroque, such as the Vancouver store (Burke, Horwood, & White, 1913).

Beaux-Arts

The other way the American presence made itself felt in the years before 1900 was in the introduction of Beaux-Arts methods of training and design and of the scholarly Neoclassicism that usually accompanied them. The French national École des beaux-arts offered a systematic training in analysis and design that Anglo-American traditions of apprenticeship could not match. After the Civil War, Americans, building on a vast scale and at great expense, recognized the system's value and organized most of their architectural schools and some practices on the Beaux-Arts pattern. The mania to organize every aspect of life and the example of the Beaux-Arts layout and architecture of the World's Columbian Exposition, of 1893, brought Beaux-Arts rigour and brought Neoclassical elegance to the fore — lessons not lost on Canadians, though some resented the "American attitude."

Pale, dignified Beaux-Arts classicism began to invade most fields of design, putting Richardsonianism to flight, so that by 1914 it was the single dominant mode of public (and much private) design in Canada. In 1901–05, McKim, Mead & White, of New York, renovated and expanded the headquarters of the Bank of Montreal, transforming John Wells's temple-form bank of the 1840s into a vestibule to a huge new banking hall with a colourful classical interior recalling that of an early Christian basilica. Soon temple-fronted banks with classical columned facades appeared as status symbols in major Canadian cities. Darling & Pearson's Canadian Bank of Commerce in Winnipeg (1910–12) and John M. LYLE's rather more delicate Bank of Nova Scotia in Ottawa (1923) are examples.

Houses rarely demonstrated the influence of Beaux-Arts classicism, though examples can be found, such as the J.K.L. Ross house (E. and W.S. Maxwell, 1908–09) in Montréal's elite "Square Mile." Public buildings of every type, however, soon fell into line. Legislatures built in the three Prairie provinces between 1908 and 1920 were domed, formally planned Beaux-Arts structures of somewhat imperial British flavour.

Federal buildings erected after 1900 — city halls, schools and public libraries — drew on the style, and, when built of red brick, a mild Queen Anne flavour was evoked. Beaux-Arts methods of composition could be adapted to styles other than classicism, as was the case in the neo-medieval Connaught departmental building in Ottawa, of 1913–14 (David Ewart for the Department of Public Works).

In the long run, the Beaux-Arts perhaps exercised its greatest influence in architectural education. Though McGill's program remained stubbornly picturesque, Arts & Crafts in orientation, the next generation of schools all adopted the systematic Beaux-Arts pattern of training by means of graduated design-exercises, normally emphasizing classical styles. This is true of the University of Toronto, which began instruction in architecture in 1890 (school opened in 1948), and the University of Manitoba, which began its architectural program in 1912.

Formal, symmetrical Beaux-Arts composition was even extended to the scale of the city by the CITY BEAUTIFUL MOVEMENT, an American offshoot of the Beaux-Arts. It sought to bring neo-Baroque grandeur and axial, symmetrical effects to the planning of civic centres and, in a few cases, whole cities. Comprehensive planning, as it was called, originated in the mid-19th-century parks movement, whose main spokesman was Frederick Law Olmsted of Boston. His work included laying out Mount Royal Park, then on the northern flank of Montréal (designed 1874–77), in a naturalistic, rather English style.

By 1900, however, rational planning was being applied to whole cities, as in Chicago in 1907–09. A plan presented in 1915 by Edward Bennett, an American architect (originally English) who had worked on that plan, for a great federal precinct lining the cliff tops above the Ottawa River, echoed Washington's formal grandeur but recommended Château imagery for Canada's capital. The year before, English planner Thomas Mawson had published an elaborate and abortive plan for Calgary which called for classical buildings in uniform rows and for an overlay of radial boulevards cutting across the grid of numbered streets and ending in neo-Baroque vistas. Little was actually implemented of either the Ottawa or Calgary plans, partly because the Great War [DB4] intervened.

Domestic Informality

So much formality was wearying in the home, as the long-lived Queen Anne Revival suggests, and the rational commercial style and learned Beaux-Arts provoked a naturalistic reaction in Arts & Crafts domestic architecture. Especially in Canada, such work usually had an English flavour, since the Arts & Crafts movement had originated as a reaction to mid-Victorian industrial Britain. After 1900, rustic — though often large and luxurious — Arts & Crafts houses and "garden suburbs" designed along free, naturalistic lines began to appear at the edge of several Canadian cities, encouraged by the radial spread of tram lines. The work of Eden Smith, born and trained in England, in Toronto, such as the Riverdale Courts garden apartments (1914–16) and several houses in Wychwood Park, is an example. So are the numerous, often large bungalow-type houses of Samuel MACLURE, built in and around Victoria and in the garden suburb of Shaughnessy Heights built on CPR lands south of the downtown peninsula of Vancouver, which soon after 1900 surpassed Victoria as BC's metropolis. Maclure's work also draws on the Craftsman and California bungalow movements in the United States.

Percy NOBBS, who came to Canada from Scotland to head the architecture program at McGill and who introduced architectural criticism to the country, emphasized Arts & Crafts values in his teaching, lecturing and writing as well as in some of his own designs. His own home in Westmount, Québec (1913–15), is an example. The Town of Mount Royal, on Montréal Island, developed by the Canadian Northern Railway to designs by landscape architect Frederick Todd in 1910–11, is an outstanding example of an early garden suburb, the origin of 20th-century Canadian suburbia.

Between 1900 and the First World War, progressive architecture in Canada was polarized between extremes of picturesque rusticity at home and rationality and formality in public, especially downtown. A theme that marked the whole period, particularly the years after 1900, was national expression. By the outbreak of the Great War, argues Kelly Crossman, many architects had come to identify expression of Canadianness as their key task in design. The search took many forms, from the proliferation of Château Style railway hotels — the building of new transcontinental lines by the Grand Trunk Pacific and Canadian Northern companies led to the building of several more of these, including Ottawa's Château Laurier (Ross & MacFarlane, 1908–12, with later additions) — to the study by Nobbs and others of Québec vernacular buildings. As with the emergence of the Group of Seven painters, these tendencies in architecture mark both maturity in Canadians' sense of identity and anxiety in the face of British imperialism and apparently irresistible cultural pressure from the powerful United States.

See also ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY, EARLY FIRST NATIONS; ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY, THE FRENCH COLONIAL RÉGIME; ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY, 1759-1867; ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY, 1914-1967; ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY, 1967-1997.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom