Bison versus Buffalo

The name “bison” is derived from Latin and means “wild ox.” It may have originated from the Baltic region, meaning “stinking animal,” referencing the smell of the bulls during breeding season.

Many people are unsure whether to refer to this species as “bison” or “buffalo.” Technically, there are no true buffalo native to North America. There are two kinds of buffalo: the cape buffalo of Africa (Syncerus caffer) and the water buffalo of Asia (Bubalus bubalis).

There are several theories about the origin of the use of the term “buffalo.” It’s suggested that when Europeans initially arrived in North America, they saw a species with a resemblance to the buffalo of Africa and Asia and referred to the bison as buffalo. Others suggest that the name is derived from the French word bœuf, also meaning ox or bullock.

Despite the technical usage of the word, people have used the term buffalo when referring to North American bison for hundreds of years and, as a result, there is a long cultural and romantic tradition associated with the name. For many Indigenous peoples, buffalo remains the name of choice. As a general rule, buffalo is often used in a cultural context, while bison is used in a scientific context.

Evolution

During the Pleistocene (11,700 to 2.6 million years ago), the northern regions of North America saw the Laurentide and Cordilleran glaciers expand, then retreat, spread again and then retreat. When these glaciers retreated, a region of exposed land, referred to as Beringia,connected Siberia with North America.

Like sea surf along a beach, Beringia was exposed, covered and exposed again. During the periods of glacial retreat, an ice-free corridor was exposed in the region east of the Rocky Mountains from Yukon to central North America, and many different species migrated south along this route. Among them were the first bison to colonize the new habitats of present-day Canada and the United States. Then, once again the glaciers would close off the migration route, effectively sealing off movement and isolating northern and southern North America once again. The bison that made it to the south continued to flourish in the central Great Plains, while those to the north of the glaciers also continued to evolve, but along a different path. Then, as the wave of ice retreated again, the different types of bison would encounter each other, hybridize, and new species would once again emerge from the mix.

There were two waves of bison to enter North America from the west. The first bison to arrive in North America travelled from eastern Siberia across Beringia between about 195,000 and 135,000 years ago, followed by the second wave 14,000 to 11,000 years ago. This species, the steppe bison (Bison priscus), originated in Asia and spread throughout lowland Europe to eastern Siberia, and eventually across the Bering land bridge to North America. It moved south into the central United States where, after being isolated by glaciation, it evolved into Bison latifrons. This was the largest bison to have ever lived, possibly weighing in at more than 2,000 kg and standing over 2.5 m tall. Environmental changes across the continent resulted in a series of evolutionary adaptations that forced Bison latifrons to slowly evolve into Bison antiquus, then Bison occidentalis, and eventually into the existing bison of North America, the plains bison (Bison bison bison) and wood bison (Bison bison athabascae).

Description

Plains Bison vs Wood Bison

Plains and wood bison are considered subspecies within the genus Bison. The long bony spines on their vertebrae create their distinctive hump profile. For both subspecies, most of their weight is carried on their front legs, making it difficult to use their front feet to dig through snow when foraging in the winter. The hump supports a structural system designed to support a massive head during months of cratering through deep snow. They use their foreheads to push the snow aside to gain access to the grass they eat.

Plains bison are the smallest bison species to have existed. Like all large mammals, bison males are larger than females. Adult males weigh an average of 739 kg, while females average 440 kg.

Wood bison are the largest of all living bison with adult bulls averaging 880 kg and females averaging 540 kg.

Distribution and Habitat

Plains bison once ranged from the Gulf of Mexico east into the Appalachians, west to the Continental Divide, and as far north as the central prairie provinces. They did not occupy British Columbia, Ontario or the eastern provinces. The core of their range was the Great Plains of central North America.

Wood bison historically ranged throughout the boreal forest from western Alaska into Yukon, northeastern British Columbia, the southwestern Northwest Territories, and the northern half of Alberta and northwestern Saskatchewan.

They shared a region of overlap in the aspen parkland belt of Alberta and Saskatchewan when some wood bison moved south and some plains bison herds moved north during the winter months. While they lived in the same region for several months, this rangeland overlap occurred outside of the breeding season. As a result, while hybridization between the two subspecies was possible, it was likely infrequent.

Diet

Both plains and wood bison evolved to eat grasses and sedges. For plains bison on the vast open grasslands, the bulk of their diet is grass, even during the winter months. Wood bison have a slightly more diverse diet that includes lichen and woody vegetation, and during the winter months almost exclusively a diet of sedges.

Both subspecies are physically adapted to a diet of low-growing plants. They have a broad row of front teeth that are designed to mow the grass in a wide swath, close to the ground. Like most other ruminants, they have a four-chambered stomach that is designed to extract the most nutrients possible from a diet high in cellulose.

Reproduction and Development

Both plains and wood bison are predator swamping animals. They evolved a reproductive cycle that floods the landscape with newborns in a very short period of time, as a method of confusing predators. This helps to ensure the survival of the calves.

The plains bison breeding season, or rut, occurs between 15 July and 15 August, with a peak in breeding activity in the middle. After a gestation period of just over 9 months, cows give birth from late April through the middle of June.

Plains bison female calves are born weighing about 16–18 kg, with males heavier at about 20–23 kg. Growth is rapid, with calves gaining more than one kilogram per day from birth to the onset of winter. Growth slows during the harsh winter months, but with new grass in the spring, they again grow rapidly.

Females usually breed during their second summer, producing their first calf when they are three years old. Females are considered mature after four years of age, and will continue to produce a calf every year until they reach about 15 years of age. They are long-lived, with records of plains bison cows attaining 40 years.

Males are physiologically capable of breeding as yearlings, but in a wild herd are not permitted to do so by the older bulls. Once a bull is about 8 years old he becomes a dominant breeding bull and will continue to breed until his mid-teens. Bulls suffer a higher mortality rate than females, due in part to the battles they fight for access to cows in the rut. As a result, most bulls do not live to reach 20 years of age.

Wood bison have the same breeding age and gestation as plains bison, but due to the higher latitude the rut is delayed by one to two weeks to match the peak in forage production. Unlike plains bison, where herds of hundreds of thousands would form during the rut, wood bison live in smaller and more isolated herds. As a result, competition between rival males is reduced and the life-or-death battles between males are less common.

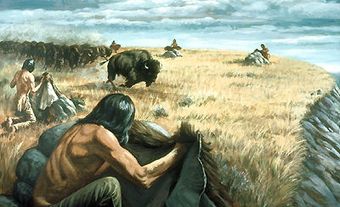

Depopulation

The depopulation of both plains and wood bison was the direct result of the European invasion of North America. The population decline in present-day Canada began with the need for meat to provision the fur traders of the Hudson’s Bay Company and North West Company, but the North America-wide slaughter was accelerated by several significant developments.

First, the development of a new hide-tanning process in Britain and Germany during the second industrial revolution (1870–1914) resulted in an insatiable need for cow hides for leather. This demand could not be supplied in Europe, so attention turned to North America’s vast herds of bison. The new tanning process made these strong hides suitable to be turned into heavy leather belts used on the innovative machinery of the time.

The ability for hunters to kill large numbers of bison was facilitated by the development of new rifles. Chief among these were the Sharps rifles, famous for their ability to kill a bison at long range with one shot. The number of bison killed by a hunter with this rifle was only limited by the number his crew could skin in a day.

There was also a concerted effort by some components of the US military to slaughter bison, a primary source of food for Indigenous people, as a means of forcing them off their ancestral lands and onto reserves. The Canadian government, under Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, also forced Indigenous people off their lands as a step towards opening the Prairies to European settlement. The rapid decline of bison was used to make Indigenous people dependent upon cattle for food, and to get that food they had to move onto reserves.

Prior to their depopulation, bison were the most abundant large mammal on the continent. The most often accepted estimate of plains bison abundance is 30 million. With an average nose-to-tail length of 1.7 metres (across all ages and both sexes), and with all 30 million lined up, they would have gone around the equator about 1.3 times. By the time the slaughter was finished in the mid-1880s, there were not enough wild plains bison left in North America to go for one city block. Nearly all of the plains bison alive today are descendants of the last 116 wild bison. Plains bison were extirpated from Canada by 1888.

Wood bison were never as numerous as plains bison, with the upper limit of their population around 170,000 animals. However, they too were subjected to heavy hunting and, following several severe winters in the late 1800s, their population reached a low of about 200.

Conservation

In Canada, the first significant step towards conserving plains bison was the purchase the Pablo-Allard plains bison herd from Montana. Between 1907 and 1909, more than 700 pure plains bison were gathered, corralled and shipped in railway cars from Montana to Elk Island National Park, Alberta. In addition to this large herd, a small herd of plains bison was established in Banff National Park in 1898, where they were maintained as a paddock display herd for almost 100 years. While that display herd was removed in 1997, a new wild population was established in February 2017, and for the first time since 1883, bison calves were born in the wild in Banff.

The plains bison in Elk Island were held there for several years while Buffalo National Park in Alberta was being fenced and prepared for their arrival. Elk Island National Park retained a small herd and these grew rapidly into one of the most successful species recovery programs in Canada. Plains bison from Elk Island have been used to establish new populations across southern Canada and provided most of the bison found on farms in Canada. Today, the North American plains bison population fluctuates between about 350,000 and 400,000 animals, mostly on farms and ranches. An estimated 1,500 to 2,000 plains bison live in conservation herds in Canada.

After their near demise in the early 1900s, wood bison made a significant recovery under the protection of Wood Buffalo National Park. From a low of about 200, the population had reached approximately 1,500 by the early 1920s. The road to recovery for wood bison was affected between 1925 and 1927 when almost 7,000 plains bison from an overcrowded Buffalo National Park were shipped north into Wood Buffalo National Park. The two subspecies hybridized and by the 1940s most of the pure wood bison had been lost due to hybridization. In 1957, a remote herd of wood bison was found, and using captured animals from this group, a herd of wood bison was established in Elk Island National Park, and another in the Mackenzie Bison Sanctuary, Northwest Territories. Wood bison from Elk Island have been used to establish new wild populations throughout their historic range in Canada, Alaska, and into Siberia. Current (2017) estimates suggest there are between 5,000 and 7,000 wood bison in conservation herds.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom