The Battle of the Atlantic, from 1939 to 1945, was the longest continuous battle of the Second World War. Canada played a key role in the Allied struggle for control of the North Atlantic, as German submarines worked furiously to cripple the convoys shipping crucial supplies to Europe. Victory was costly: more than 70,000 Allied seamen, merchant mariners and airmen lost their lives, including approximately 4,400 from Canada and Newfoundland. Many civilians also lost their lives, including 136 passengers of the ferry SS Caribou.

Battle of the Atlantic: Facts

| Date | 3 September 1939–8 May 1945

|

| Location | Atlantic Ocean

|

| Participants |

Allied powers: United Kingdom, Canada, United States, Brazil, Norway Axis powers: Germany, Italy |

| Casualties |

72,000 Allied deaths (including servicemen and merchant mariners) 30,000 German deaths |

| Canadian Casualties |

2,000 sailors (Royal Canadian Navy) 1,600 merchant mariners (Canada and Newfoundland) 752 airmen (Royal Canadian Air Force) |

The first shots on the Atlantic were fired on 3 September 1939, just hours after Britain formally declared war on Germany. Off the coast of Ireland, a German submarine, U-30, torpedoed the SS Athenia, a passenger ship en route to Montréal with more than 1,400 passengers and crew on board; 112 people were killed, including four Canadians.

The battle for control of the key shipping routes between Europe and North America had begun. German Admiral Karl Dönitz believed that disrupting or severing the delivery of food, oil, equipment and supplies would ensure that Germany would win the war. Dönitz co-ordinated a blitz on Allied shipping that would continue until the last days of the war.

Canada Joins the Battle

Canada declared war on Germany a week later, on 10 September 1939. Immediately, Canada’s navy, merchant marine and air force were thrust into the Battle of the Atlantic.

Canada’s role was primarily escort duty for the hundreds of convoys that gathered in Halifax and Sydney, Nova Scotia, for the treacherous journey across the Atlantic. Other Canadian ports, as well as the port of St. John's, Newfoundland, harboured naval and merchant vessels that joined the convoys. The first convoy, HX-1, left Halifax on 16 September 1939 escorted by British cruisers and two Canadian destroyers, HMCS St. Laurent and HMCS Saguenay.

At the time, Canada’s navy was small — only six destroyers and about 3,500 personnel, a third of whom were reservists. To meet its obligations, Canada embarked on a massive shipbuilding effort, commissioning dozens of smaller warships known as corvettes. About half the size of a destroyer and armed with only a single gun and depth charges, the corvettes, which were quick and inexpensive to build, took on a significant portion of the convoy duties.

The convoys also received aerial protection from the Royal Air Force Coastal Command, which included seven squadrons of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF). By the end of the war, RCAF planes were credited with sinking 19 German U-boats. Coastal Command, which included many RCAF crews flying British planes, accounted for more than 200 U-boat kills.

U-Boat Wolf Packs

In the early years of the war, the U-boats were clearly winning the battle. Under the command of Admiral Dönitz, the U-boats developed a deadly strategy, hunting convoys in wolf packs. Groups of submarines would stretch out across suspected convoy routes. When a submarine spotted a convoy, the call went out for the rest of the wolf pack to rendezvous in its path. Once gathered, and under cover of night, the U-boats would strike together — their torpedoes ripping into several ships almost simultaneously.

The Germans first used this tactic on 18 October 1940. Seven submarines attacked convoy SC-7, a group of 35 merchant ships and 6 escorts sailing from Sydney, Nova Scotia, to Liverpool, England. During the three-day battle, the U-boats sank 20 of the merchant ships; approximately 140 sailors lost their lives.

Canadian naval officer Lieutenant Commander Desmond Piers offered a terrifying account of what it was like to be attacked by a wolf pack. In November 1942, his destroyer HMCS Restigouche, along with five corvettes, was escorting a convoy of 42 merchant vessels when they were surrounded by at least 16 U–boats.

Sometime around midnight the attacks developed…we then entered a period of 72 hours of absolute nightmare…I’d go dashing off at full speed, as fast as the ship would go…drop depth charges…try to put that one down, but there we were surrounded by U-boats…and this went on for 72 hours. (Lt Cdr Desmond Piers)

When it was over, the Germans had sunk one third of the ships in Piers' convoy.

"Black Pit "

Many of these attacks took place in an area of the mid-Atlantic that became known as the “Black Pit” — a stretch of ocean beyond the range of Allied aircraft tasked with providing aerial coverage for the convoys.

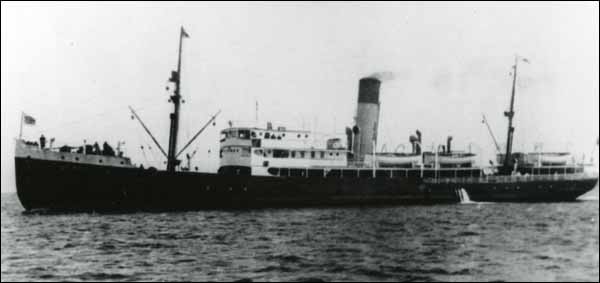

Emboldened by their submariners’ success, the German command also sent U-boats to the coastal waters of Canada and the United States, where they inflicted severe damage to ships and oil tankers sailing up the coast to join convoys assembling in Nova Scotia. In May 1942, German U-boats entered the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the inland waters of the St. Lawrence River, sinking 21 ships that shipping season, including the ferry SS Caribou. It was the first time Canada had waged war on its inland waters since the War of 1812. (See Battle of the St. Lawrence.)

The Germans were close to their goal of crippling the vital supply chain to Great Britain. Between March and September of 1942, U-boats sank almost 100 merchant ships a month. Roughly 2,000 merchant ships had been lost since the battle began, thousands of sailors had been killed and millions of tons of precious cargo lay at the bottom of the ocean.

Tide Turns

By 1943, a series of factors helped turn the tide of the battle. British intelligence, which had already cracked the Germans' Enigma code, made even further advances in this field, allowing the Allies to better track German communications and U-boat movements. New long-range aircraft were also developed that allowed full aerial coverage of the Atlantic. Britain’s Royal Navy undertook more aggressive tactics against the U-boats, forming elite hunter groups of its best anti-submarine ships to prowl the ocean searching for submarines and to aid convoys under attack.

With British ships now on the offensive, Canada expanded its escort duties and sent ships to help protect British ports. The new combined tactics worked. In 1943, U-boats managed to sink fewer than 300 merchant ships, a quarter of the number from the year before, and most of those came in the first few months of 1943. With German U-boat losses skyrocketing, the Germans scaled back their campaign for several months.

Canada’s navy, bolstered by the delivery of new, faster and more powerful frigates, formed its own hunter groups. Between November 1943 and the spring of 1944, Canadian ships sank eight U-boats.

Northwest Command

In recognition of Canada’s substantial role, the Allies put the entire northwest Atlantic — from Nova Scotia to the Arctic Circle— under Canadian control. Rear Admiral Leonard Murray was named commander-in-chief, Canadian Northwest Atlantic. He was the only Canadian to command an Allied theatre of conflict in either the First or Second World Wars.

Even though Germany never regained its success of the early years, the U-boat reign of terror was far from over. By 1944, the submarines were equipped with new technology that allowed them to run greater distances underwater, as well as with new acoustic torpedoes, which homed in on the sound of a ship’s propeller.

On 20 September 1943, while escorting a convoy, the Canadian destroyer HMCS St.Croixwas struck by two acoustic torpedoes fired by U-305. Eighty-one of its 148-crewmen survived 13 hours in frigid waters before being rescued by the British warship HMS Itchen. Two days after the St. Croix went down, the Itchen was itself attacked and sunk, with the St. Croix survivors on board. In the end, only one crew member of HMCS St. Croix survived. Among the 147 dead Canadians was the nephew of Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King.

As Canada’s escort duties continued, so did its losses. In the last year of the war, eight Canadian warships were sunk and four were badly damaged.

On 16 April 1945, just three weeks before the end of the war, the minesweeper HMCS Esquimalt was torpedoed and sunk in waters off Halifax, killing 44 of her crew. Three weeks later, its attacker, U-190, surrendered to Canadian forces. The war was over.

Merchant Navy

For years, the unsung heroes of the Battle of the Atlantic were the men and women who served in the merchant navy. When war was declared, Canada had fewer than 40 ocean-going merchant vessels. By war’s end, more than 400 had been built. Twelve thousand sailors served in Canada’s merchant navy, manning the ships that delivered the food, supplies and troops that fueled the war effort. This included men and women from Newfoundland (which was not part of Canada at that time). Thousands of men and women from Newfoundland and Labrador served with merchant navies during the war. Many served on Newfoundland ships while others worked on British ships or with the Canadian or American merchant navies.

Merchant mariners made more than 25,000 voyages in vessels that were virtually defenseless and easy prey for German submarines. Fifty-nine Canadian merchant ships were lost. One in seven of those who served lost their lives — the highest percentage of casualties among all Canadian forces.

Their sacrifice was not fully recognized until 1992, when merchant navy veterans were granted the same status as veterans of the Royal Canadian Navy. In 2003, Ottawa proclaimed the third day of September Merchant Navy Veterans Day.

Did you know?

Margaret Martha Brooke was a nursing sister during the Second World War and survived the torpedoing of the SS Caribou. For her heroism immediately after the sinking, she was made a Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE), the first Canadian nursing sister so recognized.

The

North Sydney to Port-aux-Basques passenger ferry SS Caribou was sunk by

the German submarine U-69 on 14 October 1942.

Significance

The Battle of the Atlantic was a critical part of the Allied victory in the Second World War. Canada entered the war as a small country with an even smaller navy. From a handful of ships and a few thousand personnel, the Royal Canadian Navy expanded into a major fleet, with more than 400 ships and 90,000 sailors and about 6,000 women in the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service. By war’s end, Canada had the fourth-largest navy in the world.

As demands grew to build more ships, Canada’s fledgling shipbuilding industry delivered vessels at an unprecedented rate. Employing 126,000 civilians, Canadian shipyards built 487 warships, 400 cargo vessels and more than 3,000 landing craft.

Casualties and Remembrance

But winning the battle came at a huge cost. From 1939–45 more than 36,000 Allied sailors, soldiers and airmen and another 36,000 merchant seamen lost their lives. Among those were almost 2,000 members of the Royal Canadian Navy, 1,600 Canadian merchant seamen and 752 Canadian airmen. Civilian casualties included 136 men, women and children killed when the SS Caribou ferry was sunk in the Cabot Strait. Approximately 30,000 German sailors lost their lives during the battle.

Many of those who died have no gravesite — their bodies were lost to the Atlantic. Their names are commemorated on the Sailors’ Memorial in Point Pleasant Park in Halifax. Their sacrifice is also honoured in special ceremonies held every year on the first Sunday in May.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom