Initial Encounters

Breton and Norman fishermen came into contact with Algonquian peoples — Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, Passamaquoddy, Abenaki, Innu and others — of the northeast at the beginning of the 16th century, if not earlier. The fishermen moored in natural harbours and bays to seek shelter from storms and to replenish water and food supplies. These first contacts included hostile incidents, as some Indigenous people were kidnapped and taken to France to be paraded at the court and in public on state and religious occasions.

Despite this, there were mutually satisfactory encounters as trade took place. Algonquian people brought furs, hides and fish in exchange for beads, mirrors and other European goods of aesthetic and perhaps spiritual value. Soon the Algonquian exacted goods of more materialistic value, such as needles, knives, kettles or woven cloth, while the French displayed an insatiable desire for well-worn beaver cloaks. The fur trade expanded inland from Tadoussac at the mouth of the Saguenay River and from Trois-Rivières.

In the 16th century, the French, like the English and Spanish, laid claim to lands "not possessed by any other Christian prince" based on the European legal theory of Terra Nullius. This theory argued that uninhabited, or at least uncultivated lands, needed to be brought under Christian dominion. The royal commissions made to Jean-François de La Rocque, Sieur de Roberval for the St. Lawrence region, dated 15 January 1541, and to Troilus de La Roche de Mesgouez for Sable Island in 1598 urged territorial acquisition either by voluntary cession or conquest.

French Settlement and Land Claims

By the early 17th century, as the fur trade expanded, a new policy of pacification emerged. The French chose to settle along the Bay of Fundy marshlands and the St. Lawrence Valley from which the original St. Lawrence Iroquoians had gone by 1580 — causes for the “disappearance” of the St. Lawrence Iroquoians have long been debated, with explanations ranging from warfare and epidemics to simple migration or long-cycle crop rotation. At the time, the French believed no Indigenous peoples were displaced to make way for settlers. This gave the impression of peaceful cohabitation with certain Indigenous peoples, and remained characteristic of Indigenous-French relations up to the fall of Acadia (1710) and of New France (1760), with the notable exception of the Iroquois Wars of the 17th century. Beyond the Acadian farmlands and the Laurentian seigneurial tract, Indigenous peoples continued to be fully independent, following their traditional lifestyle and customs on their ancestral lands. Royal instructions to Governor Courcelle in 1665 emphasized that "the officers, soldiers and all his other subjects treat the Natives with kindness, justice and fairness, without harm or violence."

Although France claimed sovereignty over a wide area of the St. Lawrence basin and its hinterland the French Crown also recognized that Indigenous peoples were part of independent nations governed by their own laws and customs. They were referred to as allies, not subjects. Consequently, a military tribunal adjudicated legal proceedings involving Indigenous persons and French colonists. Louis XIV’s instructions in 1665, observed until the transfer to Britain in 1763, included the provision that "the lands which [Indigenous people] inhabit never be usurped under pretext that they are better or more suited to the French."

Royal instructions in 1716 not only required peaceful relations with the Indigenous peoples in the interests of trade and missions but these also forbade the French from clearing land and settling west of the Montréal region seigneuries. In the pays d’en haut, care was taken to obtain permission from groups living in the area before establishing a trading post, fort, missions or small agricultural community such as Détroit or in the Illinois country. Following a conference with 80 Haudenosaunee delegates at Québec in the autumn of 1748, Governor La Galissonière and Intendant François Bigot reaffirmed that "these Indians claim to be and in effect are independent of all nations, and their lands incontestably belong to them." Nevertheless, France continued to assert its sovereignty and to speak at the international level on behalf of allied Indigenous nations. This sovereignty was exercised against European rivals through the allied nations, not at their expense through the suppression of local customs and independence.

Indigenous political leaders accepted this “protectorate” because it offered external support while permitting them to govern themselves and maintain traditional ways of life. The Mi’kmaq, and later the Abenaki, converted to Catholicism as a confirmation of their alliance and brotherhood with the French and resistance to Anglo-American incursions. When the Mi'kmaq eventually signed a treaty of peace and friendship with British authorities at Halifax in 1752, the Abenaki who had taken refuge in Canada rebuffed the official delegate of the governor in Boston.

Missions and Creation of Réductions

By beginning their apostolic labours in Acadia in 1611 and in Canada in 1615, Catholic missionaries dreamed of a rapid conversion of Indigenous peoples, even wondering if they might be descendants of the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel. Traditional Mi’kmaq and Innu hospitality dictated that the itinerant missionaries be well-received. The missionaries centred their evangelization efforts on the sedentary, horticultural and strategically located Huron-Wendat confederacy (see Ste. Marie Among the Hurons). Factionalism that arose out of favouritism shown to converts and epidemics that decimated the population virtually brought the mission to a close. On two occasions, the Jesuits were spared execution or exile on charges of witchcraft only by French threats to cut off the trade on which the Wendat had become dependent. Eight Jesuits, including the leader of the Ste. Marie mission, Jean de Brébeuf, were killed in the years leading up to and during the Wendat dispersals. Following the dispersal in 1648–49 by the Haudenosaunee, the missionaries turned to other groups in the Great Lakes basin, including the Iroquois Confederacy, to little effect.

Colonial agents were able to exert greater influence over Indigenous people through réductions, or reserves, established within the seigneurial tract of New France. In 1637, the seigneury of Sillery near Québec was designated a réduction for some Innu encamped nearby as well as for all the northern hunters who would take up agriculture under Jesuit tutelage. Although the Innu did not remain long, some Abenaki refugees came to settle, and finally Wendat who escaped from the Haudenosaunee conquest of their territory. Eventually there were reserves near each of the three French bridgeheads of settlement: Lorette near Québec for the Wendat; Bécancour and Saint-François near Trois-Rivières for the Abenaki; Kahnawake near Montréal for the Haudenosaunee and Lac-des-Deux-Montagnes for both Algonquians and Iroquoians (see Mohawk of the St. Lawrence Valley). This indicated a fundamental difference between the “reserves” of the French colonial period and those of the following British period. The French sought to attract the Indigenous people close to their settlements with the view to having them adopt French agricultural sedentary life. The English, in New England for example, drove Indigenous people off their traditional lands into the hinterland in order to establish agricultural holdings and permanent settlement.

Nevertheless, reserves in Canada were also relocated from time to time at ever greater distances from the principal towns, mostly because of the desire of the missionaries to stem illegal trade and isolate Indigenous converts from the temptations of alcohol, prostitution and gambling. Residents of the Kahnawake reserve, supported by certain Montréal merchants, circumvented colonial trading restrictions with Albany and New York in order to get better prices for their goods, usually furs.

The French designated those Indigenous peoples who settled on reserves under the supervision of Missionaries as “Indiens domiciliés” (resident Indians). It was often on the reserves that canoemen, scouts and warriors were recruited for trade and war. The products of the field and the hunt, as well as the manufacture of canoes, snowshoes and moccasins found a good outlet on the Québec market. At the time of the British Conquest of New France in 1760 (see Seven Years’ War), the “resident Indians” were united in a federation known as the Seven Nations of Canada. It is possible that this political organization, whose membership evolved over the years, dates back to the early days of the French regime at the time when the first reserves were created in the St. Lawrence Valley.

Official French objectives had been to Christianize and francize Indigenous peoples in order to attain their utopian ideal of “one people.” The church tried to achieve this objective through itinerant missions, education of an Indigenous élite in France, reserves and boarding schools, but in the end it was clear that Indigenous culture would survive despite these efforts. Indeed, cross-cultural influence was reciprocal; missionaries and fur traders learned Indigenous languages and adopted survival techniques.

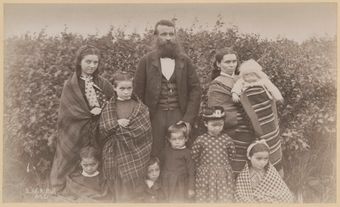

Commerce and the Métis

The Métis, from the French métisser, meaning to crossbreed, trace their origin to encounters almost exclusively between Indigenous women and Frenchmen. Though contemporary Métis are largely descended from communities around the Red River, intermarriage was common in the early contact period. Beginning with European fishermen and sailors along the Atlantic seaboard, the practice spread into the hinterland as traders and interpreters, later unlicensed coureurs des bois, and finally garrison troops came into contact with hinterland communities. Voyageurs and canoemen travelling to and from the upper country of Canada for the fur trade relied on Indigenous women to make and break camp, cook, carry baggage and serve as mistresses. Many of these unions became long-lasting and were recognized locally as legitimate à la façon du pays (in the custom of the country). Canon law forbade the marriage of Catholics with pagans, so missionaries would often instruct and baptize adults and children in order to regularize such unions. In 1735, Louis XV forbade most mixed marriages; nevertheless, the rise of mixed communities in the Great Lakes basin, particularly along Lake Superior, indicated the prevalence of the practice.

The importance of good relations with Indigenous communities for commerce, missions and military operations was highlighted in the annual transfer of colonial administration from Québec to Montréal. Upon receipt of the royal despatches from Versailles in the late spring, the governor and his officials ascended to Montréal for the summer months, where they met with the officers of the Troupes de la Marine (mostly sons of the colonial elite) posted at the interior forts, representatives of the merchants and traders and Indigenous chieftains and delegations. Responses were drafted to royal orders in the light of these deliberations, new directives were suggested and these were all sent to France by the last vessels in the autumn. The Indigenous voice was an important element in this convoluted form of royal despotism. Another aspect of the dilution of absolutism was the avoidance of the imposition of the harsh aspects of French criminal law on Indigenous defendants. As members of allied nations they would be tried by a military tribunal rather than a royal court. These tribunals simply turned them over to their tribal councils to be dealt with according to their customary practices. It was an early form of parallel justice that promoted good community relations even in interracial cases.

War and Conflict

Warfare was an aspect of Indigenous life in which the French soon became involved. Most Indigenous people in the Eastern Woodlands remained allied with France through to Pontiac’s War in 1763, with the exception of the Haudenosaunee, Meskwaki and Dakota. Champlain, by supporting his Algonquian and Wendat trading partners in 1609, earned the long-lasting enmity of the Iroquois. The French were not able to save the Wendat from destruction at the hands of the Haudenosaunee in 1648–49, nor were they able to stop incursions into their own or their western allies' territories until the Peace of Montréal in 1701. The Meskwaki were viewed as hostile from 1712 until their dispersal in 1730. The Dakota also often attacked French trading partners and allies before agreeing to a general peace settlement in 1754.

The escalation of tensions between the French and English over control of the fur trade in North America led to the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. Under the terms of the treaty, France retained access to Cape Breton Island, the St. Lawrence Islands and fishing rights off Newfoundland but ceded Acadia to the British and recognized British jurisdiction over the northern territory of Rupert’s Land and the island of Newfoundland. The Mi'kmaq, and Passamaquoddy, considered themselves to be friends and allies and not subjects of the French Crown, as well as the rightful owners of the territory ceded to the British Crown. The lack of consultation regarding the terms of the treaty, and the lack of compensation provided to the Mi'kmaq, Maliseet and Passamaquoddy upset them greatly.

France spent large sums of money for the annual distribution of the "King's presents" to allied nations. In addition, the Crown issued clothing, weapons and ammunition to Indigenous auxiliaries, paid for their services, and maintained their families when the men were on active duty. These warriors were judged invaluable for guiding, scouting and surprise raiding parties. Their war practices, including scalping and platform torture, were not interfered with as they generally fought alongside the French as independent auxiliaries. The Seven Nations of Canada, as France’s allies were known, were not forgotten by the French as the British conquest loomed large. In defeat, the French obtained favourable terms of capitulation, that their allies be treated as soldiers under arms, and that they "be maintained in the Lands they inhabit," enjoy freedom of religion and keep their missionaries. These terms were further reiterated in the Treaty of Oswegatchie, negotiated by Sir William Johnson, at Fort Lévis (near present-day Ogdensburg, New York), on 30 August 1760, and reaffirmed at Kahnawake on 15–16 September 1760.

On 10 February 1763, France and Great Britain signed the Treaty of Paris. The treaty outlined a series of land exchanges in which France handed over their control of New France. Article 4 provided for the transfer of lands in North America east of the Mississippi River to Great Britain. Under the terms of the treaty, Great Britain also gained control of Florida from the Spanish, who took control of New Orleans and the Louisiana territory west of the Mississippi River from the French.

In order to establish jurisdiction in the newly acquired Canadian colonies, on 7 October 1763, King George III and the British Imperial Government issued a Royal Proclamation outlining the management of the colonies. Of particular importance, the proclamation reserved a large tract of unceded territory, not including the lands reserved for the Hudson's Bay Company, east of the Mississippi River as "hunting grounds" for Indigenous peoples. As well, the proclamation established the requirements for the transfer of Indigenous title to the Crown, indicating that the Crown could only purchase Indigenous lands and that such purchases had to be unanimously approved by a council of Indigenous peoples.

The proclamation also provided the terms for the establishment of colonial governments in Québec, West Florida, East Florida and Grenada. The colonies were granted the ability to elect general assemblies under a royally appointed governor and high council, with the power to create laws and ordinances, as well as establish civil and criminal courts specific to the area and in agreement with British and colonial laws.

Slavery in New France

Though settlers and Indigenous people worked, traded and lived together in New France, many settlers enslaved both Indigenous and African peoples as domestic servants. Between 1671 and 1834, there were more than 4,000 enslaved people in New France and the Province of Québec. Two thirds of enslaved people were Indigenous, while the remainder were of African origin. Military officers, merchants and religious officials enslaved these people as domestic servants, rather than agricultural workers, as the economy was not plantation-based as it was in the American south.

In many Indigenous cultures, groups victorious in warfare often absorbed or took captive their defeated rivals. Often, they would exchange these captives for European goods. Though captives came from communities far and wide, all enslaved Indigenous people came to be known as Panis, after the name of the Pawnee people. Enslavement in New France was governed by the Code Noir of 1685, and was formally ended with the Emancipation Act of 1833.

Legacy

The relationship between French settlers and the Indigenous people in what became Canada was built on the foundation of commerce, with intermarriage and evangelization seen as methods toward cultural assimilation. Once usurped by the British, French colonial administrators had little contact with Indigenous peoples. However, French-speaking settlers maintained links with Indigenous communities, and continued to intermarry and form economic partnerships.

For an exploration of Indigenous relations after the fall of the French regime, see Indigenous-European Relations.

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom